Fjall is an LSM-tree based storage engine written in Rust.

LSM-trees consist of immutable disk segments (a.k.a. SSTable, SST), which are sorted lists of key-value pairs, chunked into (usually compressed) blocks (henceforth called “data block”).

Disk segments are then arranged in levels by compaction. More info here.

Today we will zoom into a disk segment specifically and look at its design.

The internal value

But before we look at the actual segment construction, let’s take a look at what a KV pair actually looks like:

type UserKey = Slice;

type UserValue = Slice;

struct InternalValue {

key: InternalKey,

value: UserValue,

}There’s some stuff to unpack here:

First off, UserKey and UserValue are just type aliases of a Slice.

A slice being some sort of immutable, heap-allocated byte array.

Right now it is backed by an Arc<[u8]>.

The internal value is a single KV-pair, consisting of key and value.

The value is just a Slice, but the internal key is actually a compound type:

type SeqNo = u64;

struct InternalKey {

user_key: UserKey,

seqno: SeqNo,

value_type: ValueType,

}The user_key is the actual key the user chooses (e.g. a UUID, or something else).

The user key decides the ordering of values in the database, and is the indexing mechanism of any KV storage engine.

The seqno is the sequence number, a monotonically increasing timestamp that describes the age of the value.

Items in the same write batch/transaction use the same seqno.

The value_type determines if the value is an insertion or deletion (“tombstone”).

We may have multiple versions of a single key in the database.

This allows MVCC (multi-version concurrency control), which is one way to implement transactions and snapshot reads.

To have a stable order, sorting by the user key alone is not enough, as the versions may end up in random order, consider this:

a:2

a:5

a:1

b:3

b:2

b:7The items are sorted by user key (before the :), but the order of the versions is random.

It would be beneficial to order versions in descending order, that way we have:

a:5

a:2

a:1

b:7

b:3

b:2When we want to read the latest items, we go to a, read a:5, then ignore the other versions and skip to b. To achieve this, we need a multi-level sort, which is easily achieved in Rust, and one of my favorite code snippets:

// Order by user key, THEN by sequence number

impl Ord for InternalKey {

fn cmp(&self, other: &Self) -> std::cmp::Ordering {

(&self.user_key, Reverse(self.seqno)).cmp(&(&other.user_key, Reverse(other.seqno)))

}

}By using (key, seqno) tuples and the Reverse struct, we can easily achieve multi-level sorting, as the Ord trait is already implemented for tuples.

Turning iterators into blocks

A disk segment is constructed when flushing a memtable. The memtable is an in-memory, ordered search tree (e.g. skip list), which gives the disk segment its inherent ordering. We can generalize a segment construction to something like:

fn construct_segment(iterator: impl Iterator<Item = KV>) -> Result<Segment> {

// ...

}

let segment = construct_segment(memtable.iter())?;The segment writer in lsm_tree works similarly, but uses an inversion-of-control-inspired design instead:

let writer = SegmentWriter::new(/* ... */);

for item in &memtable {

writer.write(item)?;

}

let segment = writer.finish()?;A simple way would be to just write out the KV-pairs one after each other:

[seqno][vtype][key len][...key...][val len][...val...]

[seqno][vtype][key len][...key...][val len][...val...]

[seqno][vtype][key len][...key...][val len][...val...]

[seqno][vtype][key len][...key...][val len][...val...]But we would need to keep track of where every KV-pair is stored, which will end up with a huge index, costing a lot of memory.

Instead, let’s group the items into blocks.

Each block has a size threshold called block_size.

We buffer the items, and when the threshold is exceeded, the block is written to disk.

The block is segmented into the BlockHeader and its content.

The block data may be additionally compressed, to save disk space.

Now we only need to keep track of each block’s end key to find any value in the segment. Because the blocks are inherently sorted, and also internally sorted (as they are constructed from a sorted iterator), we can binary search to any block quickly.

To do so, pointers are stored in memory in a search tree. Each pointer stores the offset of its corresponding data block, and can be accessed using the block’s last item’s key. Now we can binary search in memory to get a pointer to any block, reducing the number of I/O operations of finding any item to 1. Each segment is effectively its own, isolated read-only database.

In the image, if we wanted to find item key=‘L’, it’s obvious it needs to be in the middle block, because K < L < T.

Building this block index is easy: every time you write a block, look at the the current file offset and insert into the index:

// simplified for brevity

//

// buffer = &[InternalValue]

fn spill_block() {

let block = Block::serialize(&buffer, file_pos)?;

index.add(block.end_key, file_pos);

bytes_written += file.write_all(block)?;

buffer.clear();

}Persisting the block index

So, how can we retrieve the index when reloading the database from disk (perhaps after a system crash)? Reading every data block again is wasteful and could increase startup times to many seconds or even minutes, which is unacceptable.

Instead, let’s write the block index out to disk as well, after the data blocks. Let’s call that section “block index”. Now, on recovery we only need to read that portion of the file to restore the block index, scanning kilobytes, or a couple of megabytes at most for many gigabytes of user data. This is how LevelDB (and RocksDB by default) work roughly.

Because the block index can not be written to disk until the data blocks are all written, it needs to be buffered in memory.

Partitioning the block index

As the database grows, more memory will be spent on keeping the block indexes of all segments around, which directly compete for memory with cached data blocks and bloom filters. Instead of keeping the entire block index around, it would be advantageous to be able to page out parts of the block index which are rarely read to save memory. However, our current block index is a single unit, so we could only evict all of it, which is a no-go.

Instead, we group the index pointers (henceforth called “block handle”) - just like data blocks - into blocks.

To find any given index block, we do the same as before: store one pointer per block in memory. This results in a new, fully loaded index (henceforth called “TLI”, for top level index).

Now, requesting any item goes through two binary searches: the TLI, which is always fully loaded and very small, and whatever index block happens to hold the correct pointer for the data block we want to retrieve. Now, any lookup needs, in the worst case, 2 I/O operations.

The TLI itself is just an array (slice) of block handles. We can get away with not using a search tree because the index is immutable, and we get a slight performance boost for free.

struct TopLevelIndex {

data: Box<[BlockHandle]>

}Because the block handles are sorted in correct order, binary search can be used.

Rust allows binary search using slice::partition_point (there’s also slice::binary_search, but in this case, partition_point is a bit easier).

For example, his will find the handle referencing the first index block that may contain our requested key:

fn get_lowest_block_containing_key(&self, key: &[u8]) -> Option<&BlockHandle> {

let idx = self.data.partition_point(|x| &*x.end_key < key);

self.data.get(idx)

}Reverse iteration

Reverse iterating is a bit harder than just scanning forwards.

When we scan forward, we can just continue reading where we left off. But when scanning a segment in reverse, we need to read a block and then seek back to the start of the previous block. We could look up the previous block in the block index, but that would end up causing a lot of index lookups.

Instead, backlinks are stored in each block header, that way the seek position is pre-computed:

Segment trailer

Now, how do we actually find the block index and TLI block in the segment file? All blocks are dynamically sized, so we can not just jump to the correct position. And scanning through all the data blocks would be prohibitively expensive.

Instead, we store the offsets to all “areas” in the segment file in a fixed size trailer. Writing a trailer is simple because we can just append it to the end of the file, after having collected all the offsets of the other areas.

And reading a trailer is also simple, because we can simply seek to the correct position, using a negative offset:

let file = File::open(path)?;

let reader = BufReader::new(file);

reader.seek(std::io::SeekFrom::End(-TRAILER_SIZE))?;

let trailer = Trailer::from(&mut reader)?;

let meta = Metadata::load_by_ptr(&mut reader, trailer.meta_ptr)?;

let tli = TopLevelIndex::load_by_ptr(&mut reader, trailer.tli_ptr)?;

// etc...

We do not need to store a pointer to the first data block, because it implicitly starts at 0.

The meta block contains metadata of the segment, such as the block size, block count, key range, etc.

The cost of block index partitioning, and data temperature

While we can now unload parts of the block index, it seems like we just worsened overall read performance a lot. Naturally, because of its slightly more complex read path, a partitioned block will perform worse than a fully loaded one, especially for random reads.

However, there are two important things to consider here:

- We can fall back to a full index if needed

- Fully random access is rare

Think of real-life data sets:

- Most data is sorted by time to some degree

- Recent metrics, events etc. are much more important than ones from 10 years ago

- New web content often gets a spike of heavy traffic, then vanishes into the great void of irrelevancy

- Tweets (R.I.P.) are sorted by time descending, as described by the Snowflake format

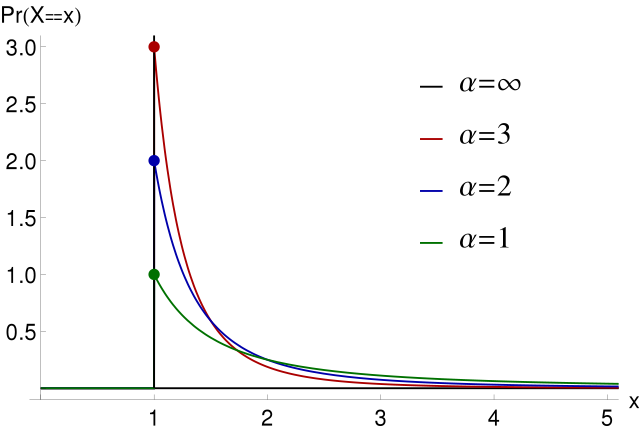

This can be modelled both by Zipfian and Pareto distributions:

The LSM-tree itself essentially models data temperature through its level architecture: smaller levels hold hotter data, and as segments are compacted down, data “cools” off. And as there tends to be much more “cold” data than hot data, the block index summed up over all segments may take up quite a bit of memory that could be used to efficiently cache more, hot data instead.

To optimize for read performance of hot data, smaller levels should use a full index, as a partitioned block index would save little memory in those levels, and smaller levels tend to store more relevant data.

Summary

I hope this blog post shed some light onto how LSM-trees arrange their data, how they retrieve data from disk, and how to trade memory usage for read performance by thinking in terms of data temperature.

Discord

Join the discord server if you want to chat about databases, Rust or whatever: https://discord.gg/HvYGp4NFFk

Interested in LSM-trees and Rust?

Check out fjall, an MIT-licensed LSM-based storage engine written in Rust.