Bloom Filter basics

Bloom filters are a probabilistic data structure to answer a membership question: is this item contained in my set?

The bloom filter returns true (probably yes) or false (definitely no). The false positive rate is often shortened as FPR.

In that regard, it works a bit like a sieve.

By adjusting the memory usage of the filter, we can control how much unwanted requests are sieved out, but we will never get a perfect 0% FPR.

The main advantage of bloom filters is their low memory usage footprint, which is decoupled from the key size. Keys are not actually stored in the data structure like you would in a hash set.

Instead keys are run through a hash function.

The resulting number i indexes into a bit array.

The bit at the calculated position determines if the item can possibly exist (1 = may exist, 0 = does not exist):

fn bloom_filter_add(bits, key) {

let hash = h(key);

bits[hash % bits.len()] = 1;

}

fn bloom_filter_contains(bits, key) -> bool {

let hash = h(key);

bits[hash % bits.len()] == 1

}The false positive rate stems from the fact that the hash function’s output is mapped a much smaller codomain (the bit array).

To reduce false positive rates because of accidental hash conflicts, multiple hash functions are used to create a key’s fingerprint. Only if all bit positions are 1, then the key may exist:

fn bloom_filter_add(bits, key) {

let hashes = [h0(key), h1(key), h2(key), h3(key)];

for hash in hashes {

bits[hash % bits.len()] = 1;

}

}

fn bloom_filter_contains(bits, key) -> bool {

let hashes = [h0(key), h1(key), h2(key), h3(key)];

hashes.all(|hash| bits[hash % bits.len()] == 1)

}A bloom filter thus can be described using four dimensions:

- bit array size (m)

- number of hash functions (k)

- number of items (n)

- false positive rate (p)

We can calculate the optimal bloom filter, using the following formulas:

n = ceil(m / (-k / log(1 - exp(log(p) / k))))

p = pow(1 - exp(-k / (m / n)), k)

m = ceil((n * log(p)) / log(1 / pow(2, log(2))));

k = round((m / n) * log(2));Example 1: To get a FPR of 1% for 1’000’000 arbitrarily long keys, we would need 7 hash functions and 1.14 MiB of memory.

Example 2: To get a FPR of 0.00001% for 1’000 arbitrarily long keys, we would need 20 hash functions and just 3.51 KiB of memory.

Double hashing

Calculating many hash functions per lookup can get pretty expensive.

lsm-tree currently uses seahash, which is already a very fast hashing function.

On my CPU, calculating a 40-character key hash takes about 5ns.

A single bloom filter lookup with 20 hash functions would cost around 100ns of pure CPU time.

We can reduce the amount of hash functions per lookup, by using double hashing:

fn bloom_filter_contains(bits, key) -> bool {

let hash0 = f(key);

let hash1 = g(key);

for i in 0..k {

let idx = hash0 % m;

if bits[idx] == 0 {

return false;

}

hash0 += hash1;

hash1 += i;

}

true

}Now any lookup only requires two invocations of our hashing function, and a bit of indexing and modulo magic.

This technique is described to be effective in bloom filters in the paper Adam K et al.: Less Hashing, Same Performance: Building a Better Bloom Filter, 2006.

Bloom filters in LSM-trees

LSM-trees are differential indexes, meaning that data on disk is never overwritten. Data is buffered in-memory, and flushed out to disk when the memory usage crosses a configurable threshold. The disk segments are immutable, sorted flat files of key-value pairs.

When searching a value in the tree, multiple segments will likely need to be checked. This may involve multiple I/O operations, decreasing read throughput. If the key does not exist, these superfluous operations can be minimized by using a bloom filter to check if there is any point in reading from disk at all. The downside is somewhat higher memory usage.

As more data arrives, segments may need to be merged & rewritten (compaction), to keep read performance acceptable. The are two major compaction strategies: Leveling & Tiering.

Leveling

Leveling initially stores flushed segments in L0. These segments may have overlapping key range, which is detrimental for performance. If too many segments are kept in L0, they are merged into the next level into fixed-size segments (default = 64 MiB), that are non-overlapping. This makes sure a point read only ever needs to check a single segment per level for data.

When that level grows too large, parts of it are merged into the next level, which is N times larger (default N = 8). That means there are up to 8 times more segments in L2 than L1. This strategy makes the key range increasingly more granular because the level size increases exponentially while the segment size is fixed.

The worst-case amount of bloom filter lookups in a leveled LSM-tree is L0_segments + (level_count - 1) because on every level after L0 segments are disjoint, so only one can be a candidate containing the searched key.

Tiered

Tiered compaction simply merges together an entire level and puts the result into the next level, creating increasingly larger segments. This improves write performance at the cost of read performance: because segments may be overlapping in any level, more segments may need to be checked per level (worst case: all segments). Using bloom filters becomes much more important to minimize disk I/O for keys that do not exist. This inadvertently increases the amount of hashing required:

The worst-case bloom filter lookups in a tiered LSM-tree is simply segment_count, with segment_count being O(log n), where n is the amount of items in the tree.

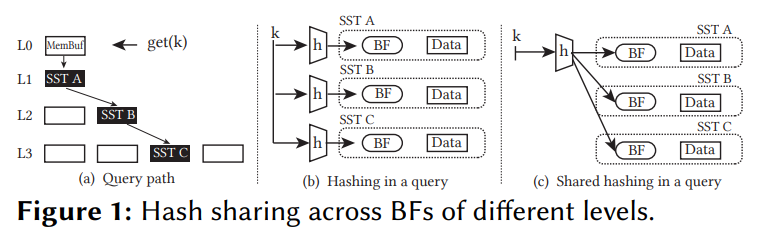

Hash sharing

When checking more than a couple of segments, CPU time of repeated hashing becomes non-trivial.

As shown in Zichen Zhu: SHaMBa: Reducing Bloom Filter Overhead in LSM Trees, 2023 by only computing the hash(es) of the requested key once, and sharing that hash across all necessary segments effectively reduces the hashing time complexity to O(1):

The key observation is that for a specific query, the same hash digest calculation is repeated across levels. The BFs are different across levels (they have indexed different elements). However, calculating the hash digest is repeated for every queried level until finding the matching key or the tree is entirely searched. Thus, to mitigate this overhead, we share the hash digest calculation across levels by re-engineering the BF implementation and allowing the BFs residing in different levels to work in concert during the course of a single query (Fig. 1). As a result, the hashing cost stays constant regardless of the number of levels.

Implementation in lsm-tree

Implementing hash sharing in lsm-tree confirms the paper’s idea:

Without hash sharing, checking more than 24 segments can easily cost more than 1µs of CPU time, at which point it may become slower than simply reading from a SSD. And performance of longer keys suffers even more because keys are not truncated before the hashing phase.

The implementation itself is very straightforward.

The BloomFilter struct was extended by a contains_hash method that takes two hashes of a key (for double hashing, called CompositeHash):

pub fn contains_hash(&self, hash: CompositeHash) -> bool;The key hash can be calculated using BloomFilter::get_hash, which is a static method that returns the required CompositeHash for the given key.

The disk segment struct (Segment) has a method called Segment::get:

pub fn get<K: AsRef<[u8]>>(&self, key: K, seqno: Option<SeqNo>) -> Result<Option<Value>>;which checks if the key can possibly be contained in the segment by checking its key range and then its bloom filter.

The Segment struct has been extended by Segment::get_with_hash to allow using a pre-computed hash:

pub fn get_with_hash<K: AsRef<[u8]>>(&self, key: K, seqno: Option<SeqNo>, hash: CompositeHash) -> Result<Option<Value>>When serving a point read, the Tree struct checks each eligible segment (pseudo-code):

for segment in &self.segments {

let maybe_item = segment.get(&key, seqno)?;

if let Some(item) = maybe_item {

return Ok(Some(item));

}

}which has been modified to pre-compute the given key’s hash and reusing it across all segments it visits:

let key_hash = BloomFilter::get_hash(key);

for segment in &self.segments {

let maybe_item = segment.get_with_hash(&key, seqno, key_hash)?;

if let Some(item) = maybe_item {

return Ok(Some(item));

}

}This optimization comes at no cost, so it will be internally be used in lsm-tree from version 1.1.2 onwards.

Discord

Join the discord server if you want to chat about databases, Rust or whatever: https://discord.gg/HvYGp4NFFk

Interested in LSM-trees and Rust?

Check out fjall, an MIT-licensed LSM-based storage engine written in Rust.