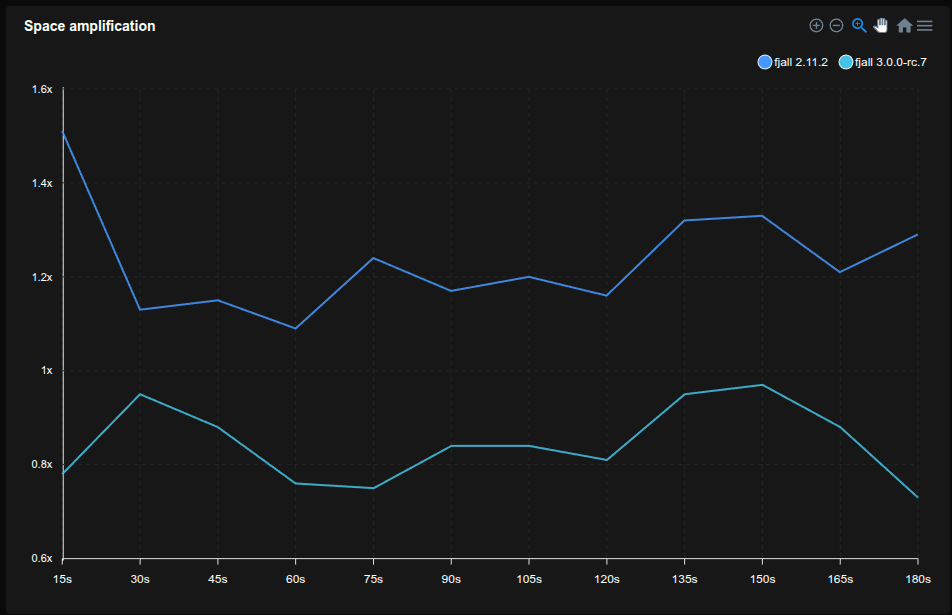

Version 3 is the future-proofing, and by far largest release for Fjall.

Fjall is a log-structured embeddable key-value storage engine (think RocksDB) written in Rust. Version 3 features better performance for large data sets, improved memory usage, more extensive configuration, and a new disk format made for longevity and forwards compatibility, plus fully revamped APIs. As of now, I believe Fjall v3 is the most capable Rust-based storage engine out there.

This post is long and would not want my worst enemies to have to read through all of it, so if you only care about benchmarks, here they are. Otherwise, here is a soundtrack for the next 40-or-so minutes.

Short LSM-tree primer

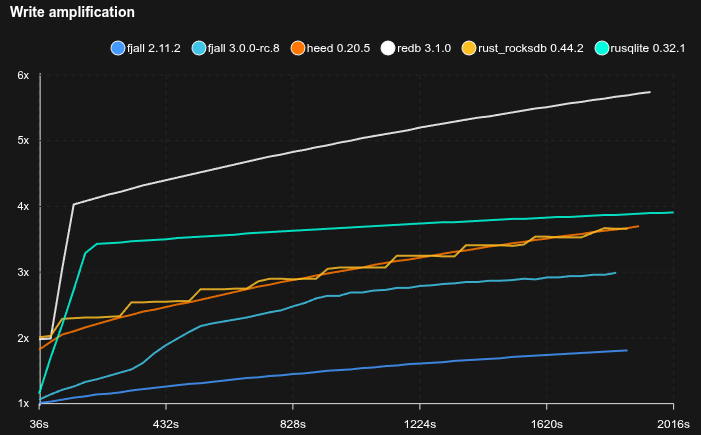

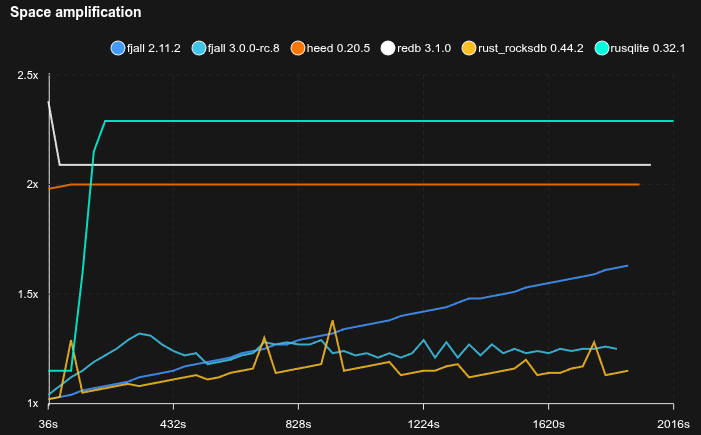

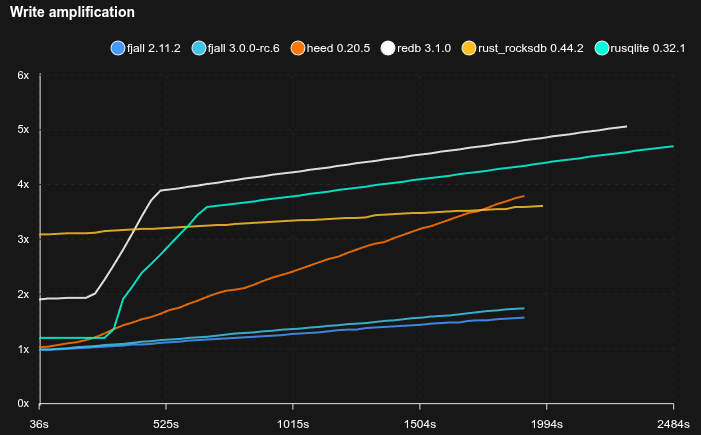

Like LevelDB, RocksDB and other similar storage engines, Fjall uses log-structured merge (LSM)-trees, providing high random write throughput, and low disk space usage, compared to typical B-tree implementations.

LSM-trees operate on immutable, sorted disk files (we will call them tables) to provide an ordered, persistent key-value map.

Table files are densely packed (and optionally compressed per block), providing very high disk space utilization (low fragmentation). Because files are only written in batches, only sequential I/O is used; which is both advantageous for SSDs and HDDs, and provides low write amplification when writing small values (e.g. timeseries data, or small database rows). Furthermore, because data is never organized eagerly, writing into an LSM-tree does not perform random read I/O (which can heavily slow down writes, especially when the data set does not fit into RAM).

Because simply amassing tables will degrade read performance, tables are merged together into disjoint “runs” of tables (simplifying here).

By using exponentially increasing capacities per level (one level is one “run”), we get a O(log N) number of levels, so O(log N) reads.

V3 started out as a rewrite of the block format, but essentially ended up being a rewrite of the whole codebase.

Revamping the block format

The old block format was really simple and naive.

Basically each data block was just a Vec<KV> serialized to disk.

This requires deserializing the entire block on read.

While that gives really fast reads in blocks, and needs no additional metadata, it requires a lot of upfront work.

If a workload is read I/O heavy (e.g. large data sets), this would cause higher CPU usage, high tail latencies, and higher memory usage.

Also deserialization takes O(n) time, which makes large block size less attractive.

The rationale behind this was: it was simple, easy to write (even in safe Rust), and… it was fairly old code. Also it surprisingly performed decently for smaller block sizes.

But not deserializing items needs some information embedded into blocks to be able to quickly find items in it.

When loaded from disk, a block is now always a single heap allocation; basically one big Vec<u8>.

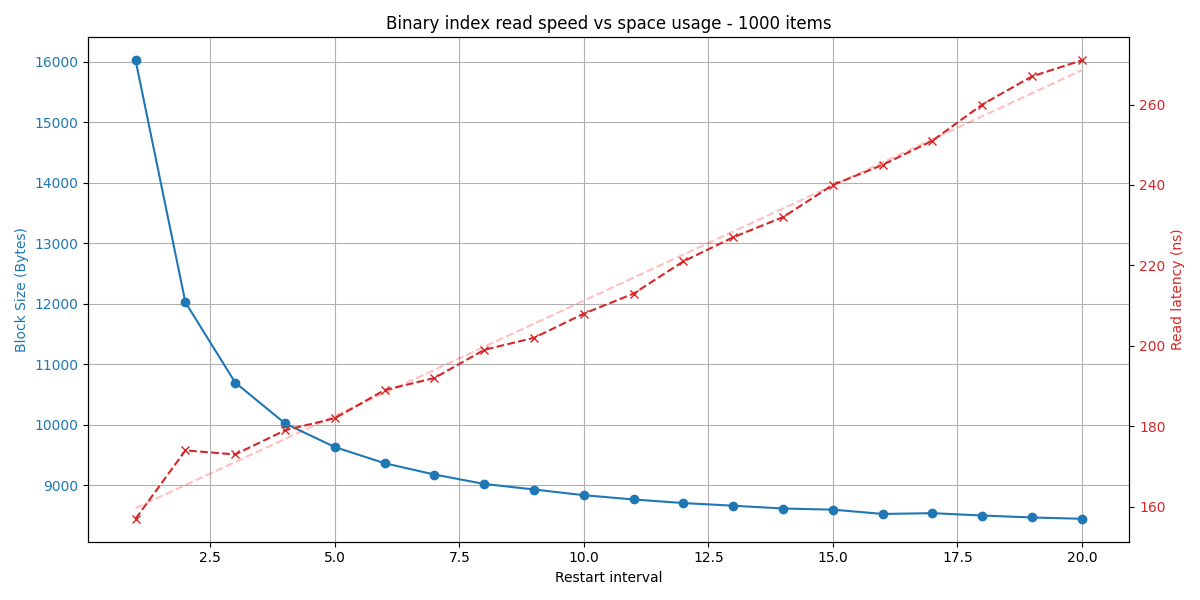

Key-value tuple are still densely packed next to each other; however, every block now has an embedded index for binary search.

Every so often, a KV’s offset is sampled and saved into the index, creating a sparse index.

If the block is <=64 KiB (likely) in size, the index pointers are stored as u16; otherwise u32.

For u16s and the default sampling interval (restart_interval) of 16, that means 2 bytes per 16 items -> 1 bit per item of additional space overhead.

Now that each block has become a single allocation, does that mean the optimizations in 2.6 have become more or less nullified? When it comes to memory usage, for the most part, yes. Because allocations are now always very large (uncompressed blocks are typically 4 - 64 KiB), the relative overhead of an allocation is very small. However, we still take advantage of the fact byteview allows us to allocate a reference-counted, non-zeroed buffer in one allocation; both to make block loads faster (by not zeroing the buffer, which can only be done using unsafe code), and have the possibility to return a subslice without additional heap allocation (only a single atomic FAA).

Many of the core components are now also fuzz- and mutation tested.

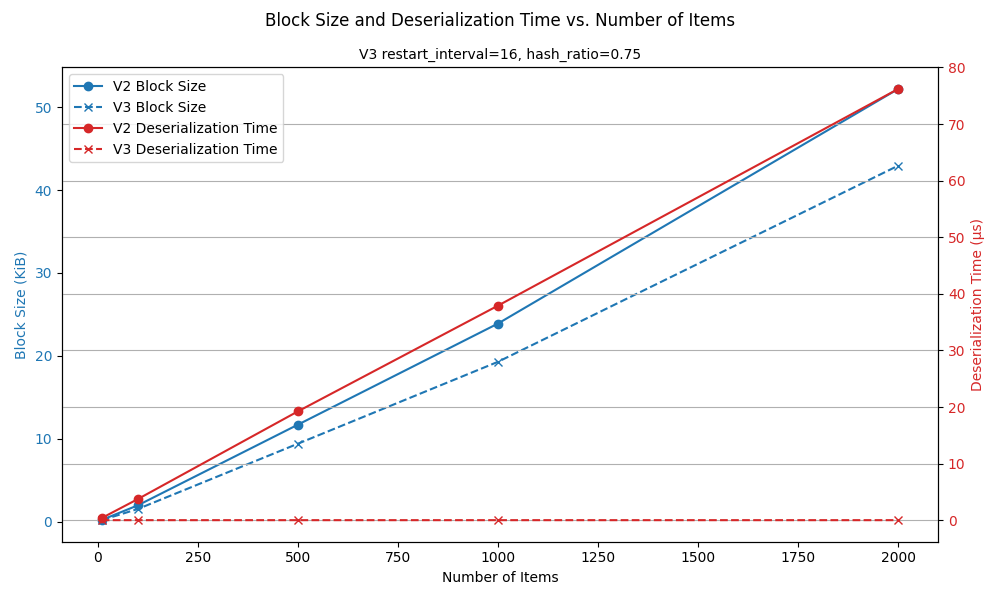

Note that this benchmark ran on an i9 11900K - slower CPUs will probably take even longer, making the jump from V2 to V3 even more noticeable.

Block read path

When searching for a key, we perform a binary search over the binary search index. Each pointer needs to be dereferenced; the pointee’s key needs to be parsed and compared to the searched key. When the binary search finds the highest candidate restart interval (the last restart head that has a key <= searched key), it performs a linear scan to (hopefully) find the requested item.

As you can imagine, the binary search & on-the-fly parsing adds some overhead to the search, however the benefits far outweigh the additional CPU overhead:

- blocks become a single heap allocation -> less memory fragmentation, and lower overhead (2x - 5x for smallish keys & values); pressure on memory allocator is reduced a lot

- deserialization is completely skipped, making uncached block reads much faster (2x-100x, depending on the block size and item count)

- more memory and space can be used to pay for more competitive read performance, so we gain more flexibility

Prefix truncation

Keys are lexicographically sorted, meaning common prefixes will sit next to each other, e.g.:

user1#created_at

user1#id

user1#name

user2#created_at

user2#id

user2#name

user3#created_at

user3#id

user3#namePrefix truncation would look something like this:

user1#created_at

id

name

2#created_at

2#id

2#name

3#created_at

3#id

3#namewhich can save a lot of space, especially for longer compound keys.

However, it inherently introduces a coupling of locality.

If we wanted to get the last item, we would need to get the first item first to get its key, then scan to the last item, and calculate the final key (user3#name).

For that reason, restart points are stored with the full key:

user1#created_at | RESTART

id

name

2#created_at

2#id

2#name

user3#created_at | RESTART

id

nameIn this example, we could jump to user3#created_at, then scan to the end, as explained above.

Consider a different example, where we store Webtable-like records:

com.android.developer/reference/#lang -> EN

com.android.developer/reference/androidx/constraintlayout/packages#lang -> EN

com.android.developer/reference/packages#lang -> EN

com.android.developer/reference/reference/android/databinding/packages#lang -> ENbecomes:

com.android.developer/reference/#lang -> EN

androidx/constraintlayout/packages#lang -> EN

packages#lang -> EN

reference/android/databinding/packages#lang -> ENsaving quite a few bytes.

But compression takes care of that!

Well kind of, yes, but only for blocks that reside on disk or in kernel cache. For uncompressed blocks in the block cache, truncated keys can save a lot of space, making it possible to fit more blocks into the block cache.

Block hash index

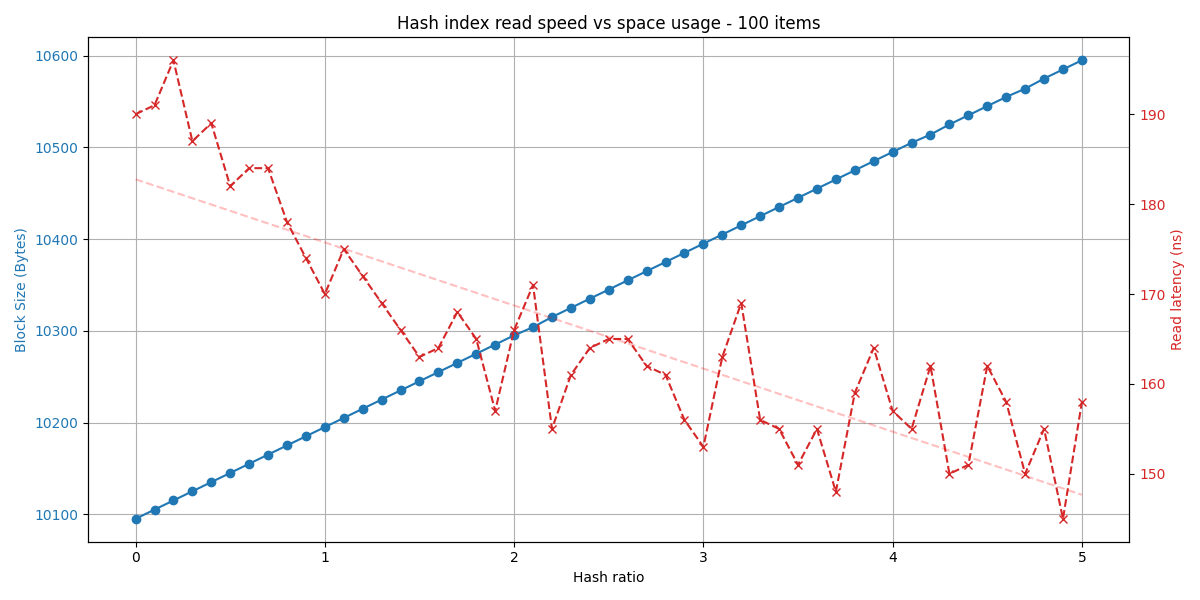

Blocks can also additionally use hash indexes to skip the binary index search when performing point reads.

The hash index is a compact hash map embedded into a block.

Each key is mapped to a bucket.

A bucket is 1 byte in size, and starts out as FREE.

Mapping a key means storing the index of its restart interval.

When another key is mapped to an already-mapped bucket, the bucket is marked as CONFLICTed.

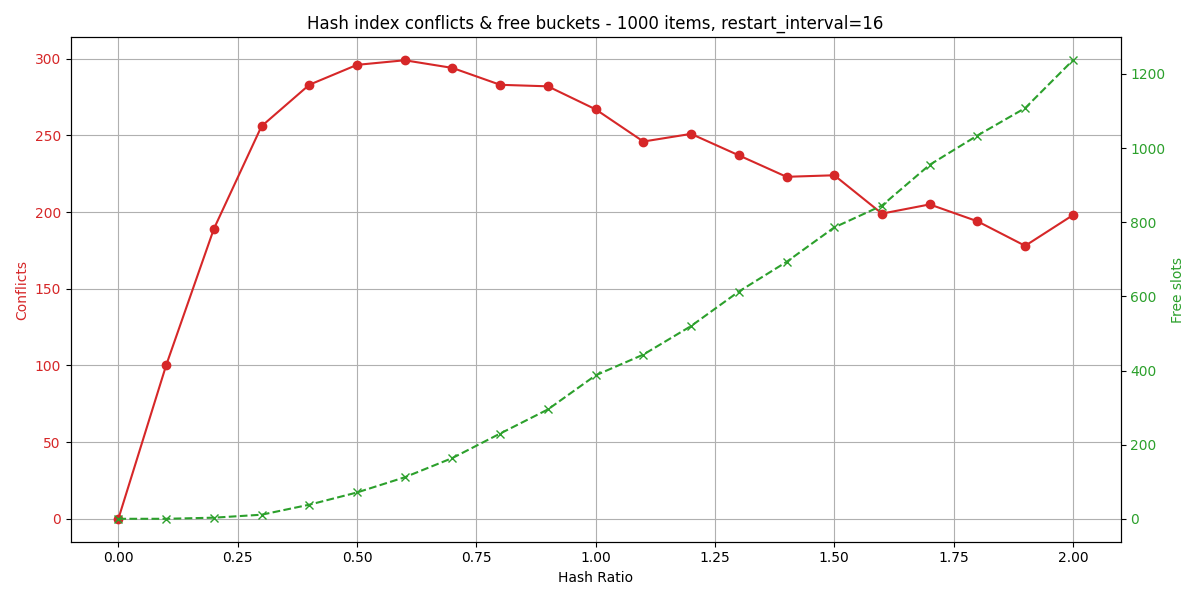

Because of these two special flags (FREE, CONFLICT), we can reference up to 254 pointers = 4064 items (with default restart interval = 16).

The number of buckets is calculated using items * hash_ratio.

To perform a point read with the hash index, the searched key is hashed and its corresponding bucket is accessed.

If the bucket is conflicted, we immediately fallback to binary search.

Otherwise, we take the bucket value = N, and lookup binary_index[N].

Then we simply linearly scan to find the requested item as before.

RocksDB uses the term “hash utilization ratio”, meaning keys / buckets; a lower number means more buckets, so generally better read performance.

We will use the inverse of the “utilization ratio”, meaning our hash ratio is 1 / hash_util_ratio; a higher number means more bytes (and thus buckets) per key, so better read performance.

In a fully cached read-heavy workload, the hash index may help improve searching through blocks.

Note that this benchmarks uses 16K blocks while redb uses 4K blocks, and a less complex page format, so inherently searches are going to be slower for fjall 3.

However, with a hash ratio = 8.0, we can recoup some read performance:

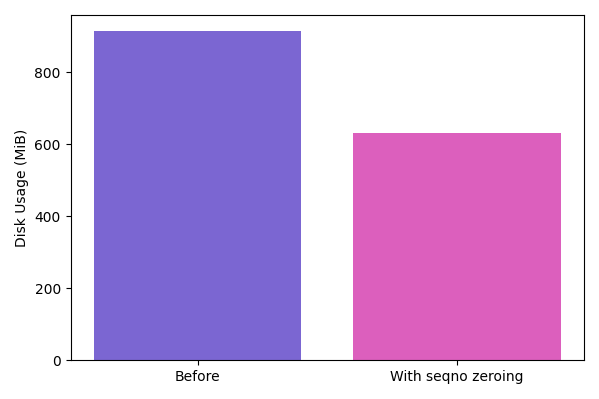

Shortening sequence numbers

Sequence numbers (seqno) are the basis for MVCC (multi-version concurrency control), which allows snapshot reads. Seqnos are monotonically increasing, so using varint-encoding for them will eventually end up being less and less attractive.

To make the varint encoding more efficient again, compaction will reset the sequence numbers to 0 (which will be encoded in a single byte), if no snapshot reads can possibly be affected by it. This can save some space when working with small keys and values (e.g. time series data, or secondary indexes with empty value).

Even though this can only performed on the last level, it still allows shortening sequence numbers of ~90% of KVs.

Versioning

This is long overdue - like RocksDB, the internal structure of the LSM-tree is now held in a (Super)Version.

A Version is a point-in-time state of the LSM-tree’s tables (and blob files, if they exist).

Whenever a compaction changes the level structure or a flush adds a new table, a new Version is created copy-on-write-style.

Old versions are only deleted once it is safe to do so, i.e. when there is no read snapshot holding that version anymore.

Only then can tables that were compacted away be actually freed from disk.

Together with this change, value-log, which was a standalone crate for the… value log implementation, has since been moved into lsm-tree.

This makes handling the list of blob files much easier because we can store them in the same Version, which makes it easier to reason about operations that change blob files (flushes and garbage collection, see next chapter).

Together with this change, the Tree now uses a single coarse RwLock instead of three (Memtable, Sealed Memtables, Version).

This is generally refered to as a SuperVersion in RocksDB terminology.

This reduces lock access costs from 3 to 1, but also makes locking simpler in general (no more lock orders).

Also, preparing compactions previously held a write lock to the levels for serializability, which shortly blocked incoming reads; now, preparing compactions do not affect readers at all, while serializability is achieved using a write lock that is only taken by the compactors.

Unlike RocksDB, snapshot reads are not affected by compaction filters or drop_range ("DeleteFilesInRange") operations.

Key-value separation, redux

2.0 introduced the first implementation of key-value separation. Key-value separation, as proposed in the WiscKey paper, separates large values from its keys into tertiary data files (the value log), (massively) reducing compaction overhead when large values are stored in the LSM-tree. Instead of a single value log as used in the paper, we used the same principle as RocksDB’s BlobDB or Titan: store blobs in immutable, sorted files (blob files). To reclaim space, those files are sometimes rewritten (during a garbage collection process), getting rid of unreferenced (garbage) blobs.

Choosing blob files to garbage collect was performed somewhat similarly to BadgerDB: collect statistics about blob fragmentation for each file and then trigger a GC process. The GC rewrites the given blob files and rewrites new blob files with garbage removed, and inserts updated pointers (vHandles) into the LSM-tree. To determine whether a blob is actually unreferenced, it queries the LSM-tree to check if the pointer for that key still points to that blob.

Until now, the blob GC process needed manual care to start this mark-and-sweep style GC. Also, the GC was basically stop-the-world, plus the GC scans would not scale unless the index tree was sufficiently small or scans were somewhat infrequent.

Now, a scheme more similar to RocksDB’s BlobDB is used: the compaction process is used to collect statistics about fragmentation (by counting blobs that are updated/removed), and then blobs are relocated directly during a compaction.

This removes the need to store back the new vHandles into the “top” of the LSM-tree, making it interfere less with foreground work (user transactions/inserts/reads).

Also it is easier to reason about because all the blob GC mechanisms use the Version system.

Ultimately, this completely removes the need for manual work to do blob GC; instead, there are garbage collection parameters that can be tweaked and will be used to kick off GC during compactions.

SFA: Simple file archive

While we lost value-log along the way, there’s a new crate in town:

SFA (Simple file archive) is a minimal, flat file archive encoding/decoding library, and used as file scaffolding for table, blob and version files in lsm-tree.

Think of it as a zip-like archive file (without compression), but extremely minimal.

To get an idea, here’s a pseudo table being written:

use sfa::{Writer, Reader};

use std::io::{Read, Write};

let mut writer = Writer::new_at_path(&path)?;

writer.start("data")?;

// write data blocks (writer is a std::io::Write instance)

writer.start("index")?;

// write index block

writer.start("filter")?;

// write filter

writer.start("meta")?;

// write table metadata

writer.finish()?;To retrieve, let’s say, the table metadata, we do:

let reader = Reader::new(&path)?;

let handle = reader.toc().section("meta").unwrap();

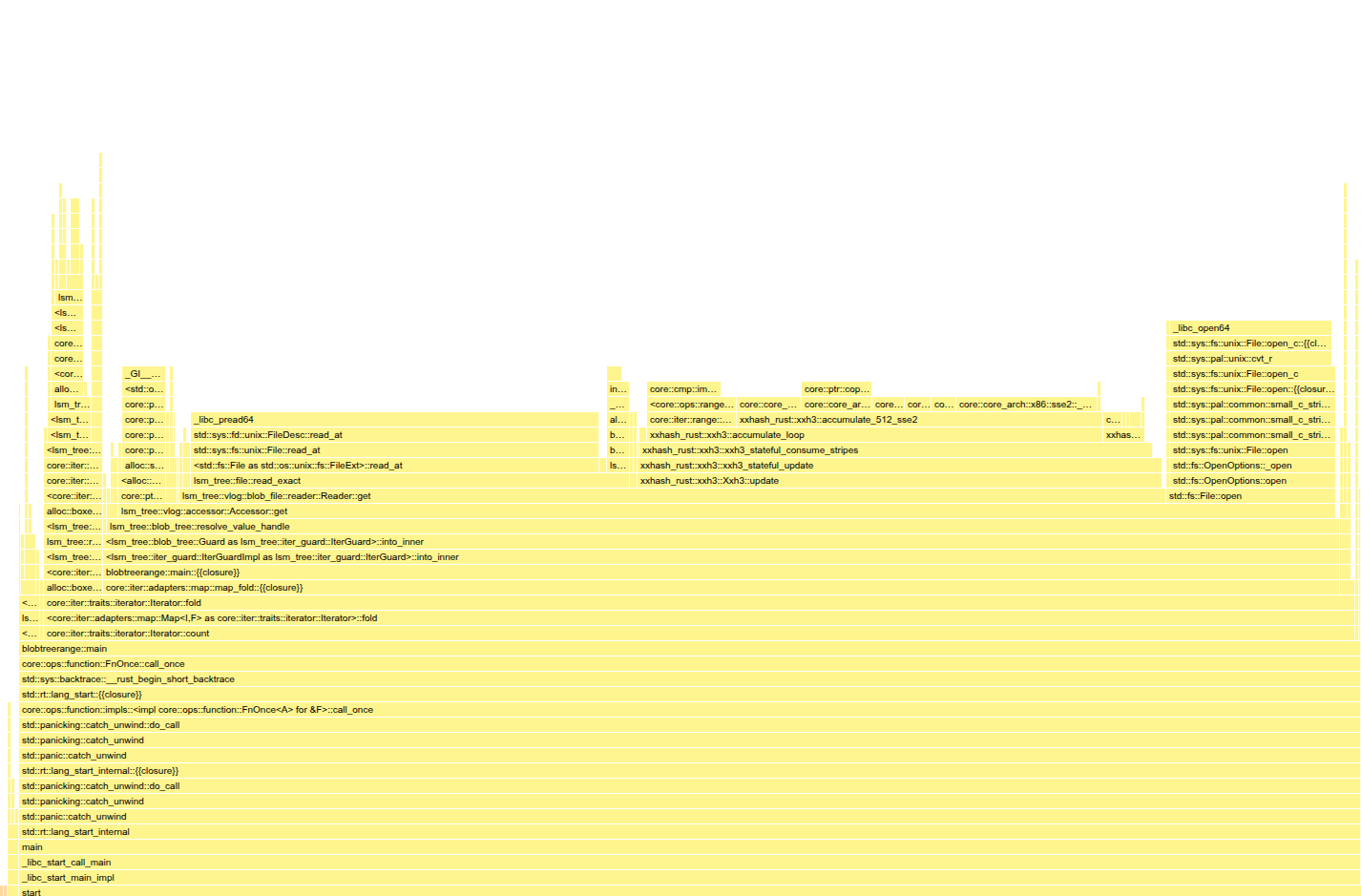

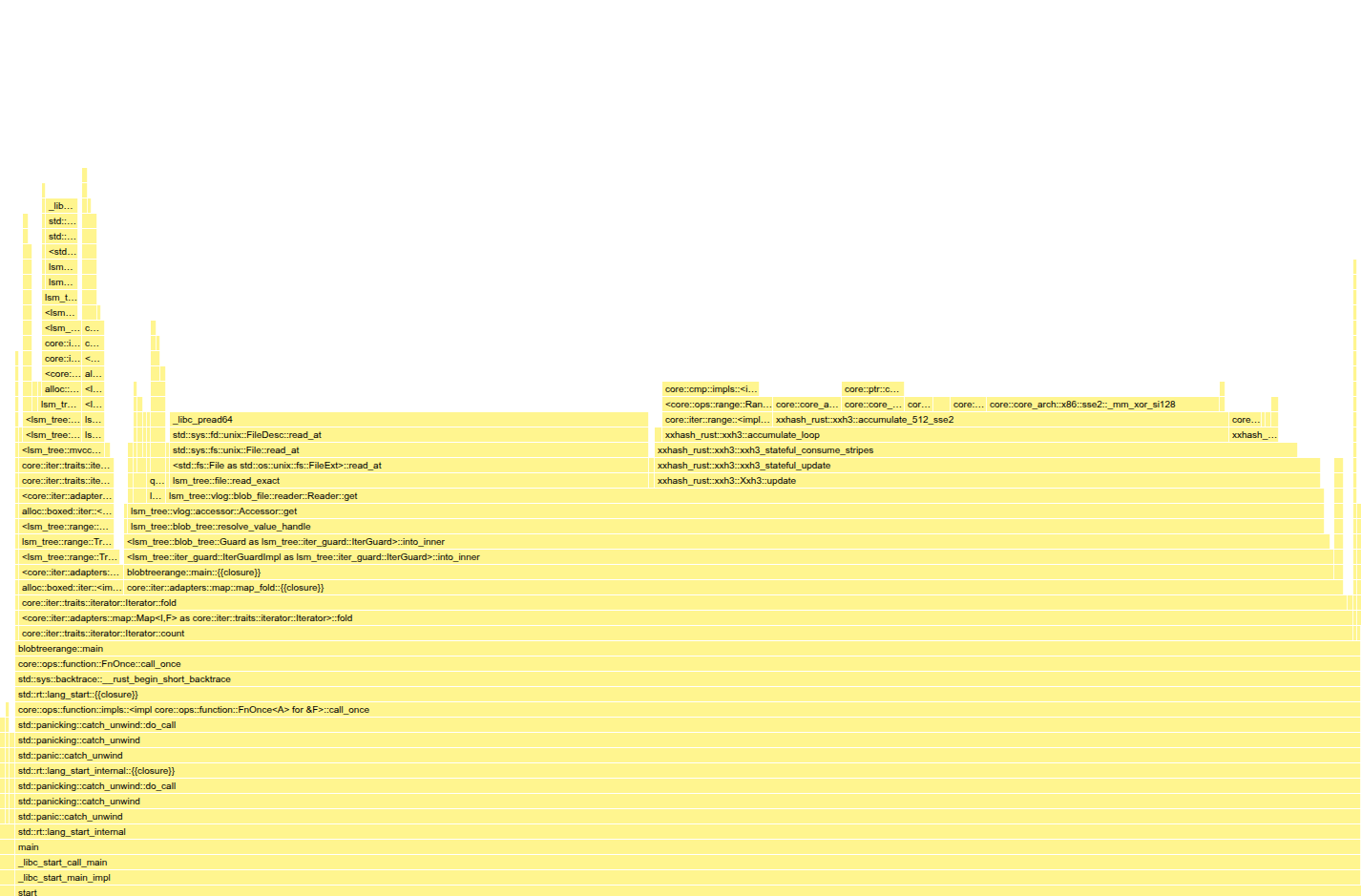

let meta = parse_metadata(&path, handle.pos(), handle.len())?;And that’s it really! SFA takes care of keeping track where sections start in a file and builds an index (table of contents/ToC) that can be queried later on. The ToC is additionally protected by a 128-bit XXH3 checksum.

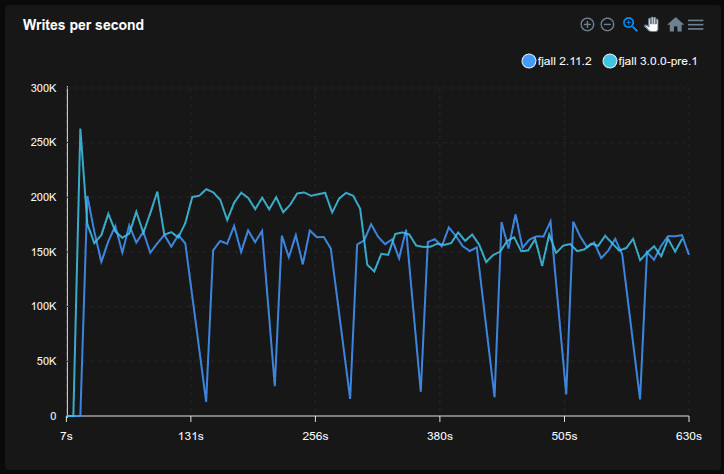

Reworked messaging & backpressure

To satisfy global write buffer size, journal and memtable limits, flush memtables to table files and further compact tables, fjall uses background worker threads.

In v2, this was kind of a mix of semaphores, queues and brute-force checking of thresholds.

In very write-intensive workloads, the v2 backpressure system could misbehave, and overload the messaging system, similar to an interrupt storm.

v3 has been massively reworked to use a more robust thread pool with messaging (currently) using bounded flume queues, and less aggressive backpressure (while still trying to stay within threshold).

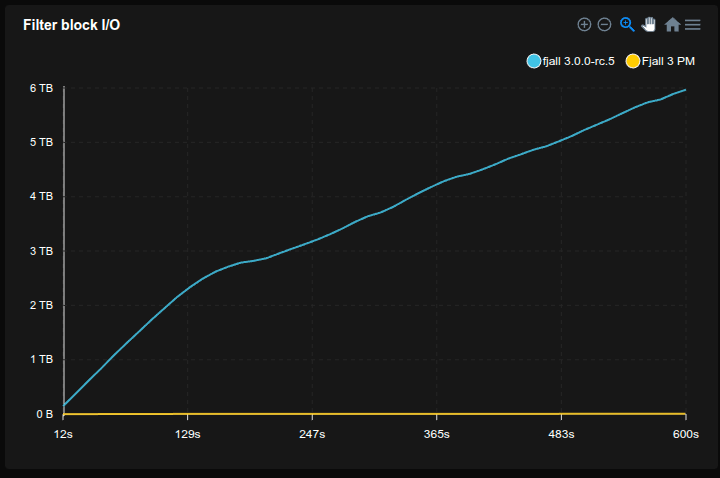

Partitioned filters

V2 already had partitioned (two-level) block indexes implemented; V3 now also supports partitioned filters.

Partitioned filters work similarly to partitioned indexes: instead of having a single filter block, the filter is cut into partitions, and a top-level index is loaded instead. When searching for a key, the index lookup tells what filter partition to load and check for key existence.

This way:

- filters can be partially paged out

- a cache miss only loads a filter partition (e.g. 4K) instead of the entire filter

For now, the top-level index is always loaded, because it is much, much smaller than the filter. But in the future - for extremely large databases - paging out the top-level index could also be a possibility.

New iterators API

Up until now, the iterator syntax could not really represent key-value separation.

For instance, if we wanted to get the list of keys of a prefix in V2:

let keys = db.prefix("user1\0")

.map(|kv| kv.map(|(k, _)| k))

.collect::<Result<_>>();This would end up loading all blobs as well, because prefix() returns all tuples (key + value) eagerly.

To combat this, it would require specialized APIs for key-value separated trees, such as:

let size = db.prefix_size("user1#").map(Result::unwrap).sum();

let keys = db.prefix_keys("user1#").collect::<Result<_>>();

let values = db.prefix_values("user1#").collect::<Result<_>>();

// ... and the same for range_*Introducting essentially 8 (!) new functions across the code base. Down the line, adding those functions would require around 24 new functions (tree API + Fjall Keyspace API + Fjall Transaction-Keyspace API), increasing the API surface a lot.

Also, they still do not really allow to decide whether to load a value dynamically for a given key or not.

Instead now, iterators return a Guard struct, that allows accessing fields, i.e.:

for guard in db.prefix("user1#") {

let k = guard.key()?; // does NOT load blob -> faster

eprintln!("found key: {k:?}");

}There are some getters to choose from:

trait Guard {

fn key(self) -> crate::Result<UserKey>;

// ^ does NOT load blob

fn value(self) -> crate::Result<UserKey>;

// ^ loads blob

fn into_inner(self) -> crate::Result<(UserKey, UserValue)>;

// ^ loads blob

fn size(self) -> crate::Result<u32>;

// ^ does NOT load blob

fn into_inner(self, pred) -> crate::Result<Option<(UserKey, UserValue)>>;

// ^ maybe loads blob, see below

}This works for all iterators (iter(), range(), prefix()):

for guard in db.iter() {

let k = guard.key()?; // does NOT load blob -> faster

eprintln!("found key: {k:?}");

}

for guard in db.range(lo..hi) {

let k = guard.key()?; // does NOT load blob -> faster

eprintln!("found key: {k:?}");

}

for guard in db.prefix("user1#") {

let k = guard.key()?; // does NOT load blob -> faster

eprintln!("found key: {k:?}");

}Furthermore, we can conditionally load blobs based on the key:

for guard in db.iter() {

if let Some(kv) = guard.into_inner_if(|key| key.ends_with(b"#html_body"))? {

// does not load blobs that are not suffixed by "#html_body"

eprintln!("=> {kv:?}");

}

}Revamped transaction APIs

Fjall has 2 “modes” for transactions: single-writer transactions, with a single writer and non-blocking readers, and serializable snapshot isolation using optimistic concurrency control.

Previously these could be toggled by feature flags, however these are now simply exported as their own types, reducing the number of feature flags by 2.

Additionally, write transactions now implement a Readable trait which is also implemented by snapshots/read transactions; this allows passing write transactions into functions that normally expect read transactions, e.g.:

use fjall::{Readable, Result};

fn do_something(tx: &impl Readable) -> Result<()> {

todo!()

Ok(())

}Checksumming

By default, block & blob loads will now perform a 128-bit xxh3 checksum check when reading from disk. While sacrificing a bit of CPU when loading data from disk or OS page cache, this makes it very unlikely to read corrupted data from a storage medium.

Corruptions are real; they happen, though rarely:

Based on our measurements, corruptions are introduced at the RocksDB level roughly once every three months for each 100 PB of data.

Changing the keyspace-partition terminology

Originally, Keyspace being called like that was inspired by Cassandra’s Keyspace -> Column Family naming.

Column Families imply storing columns, but as a key-value store, we have no idea what the user is storing.

So “column families” were instead called “partitions”, because you can use them to partition your data across differently configured LSM-trees.

However, it makes more sense for the top-level object to be called Database. Then, a Partition is a Keyspace, because it is its own isolated key space.

Migrating should be pretty easy:

- Replace all “Keyspace” with “Database”

- Replace all “keyspace” with “database”

- Replace all “Partition” with “Keyspace”

- Replace all “partition” with “keyspace”

Also, opening a DB has changed slightly from:

let keyspace = Config::new(path).open()?;

let partition = keyspace.open_partition("name", Default::default())?;

// or

let keyspace = Config::new(path).open_transactional()?;

// ...to

let db = Database::builder(path).open()?;

let keyspace = db.keyspace("name", Default::default())?;

// or

let db = TxDatabase::builder(path).open()?;

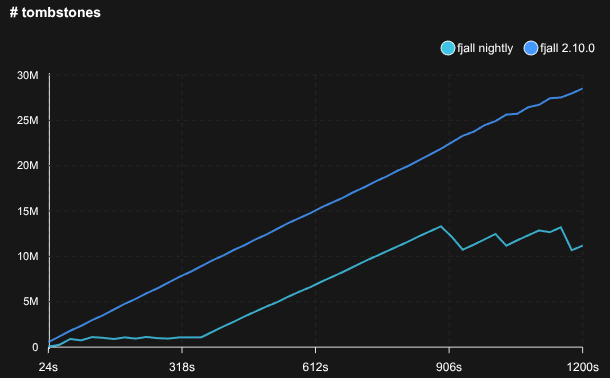

// ...Less tombstones

The Leveled compaction strategy has been reworked to (logically) promote levels into L6 immediately. The old implementation would get tombstones stuck in the middle levels and never be able to clean them up.

Caching blob file descriptors

Previously, reading an uncached blob would always require a fopen() syscall, which could account for a considerable amount of time when the same blob file is accessed multiple times.

Unlike LSM-tree tables, blob file descriptors were not cached.

Now blob file descriptors will be cached in the global DescriptorTable, saving ~15% time in this benchmark:

Thanks to @k-jingyang for originally implementing file descriptor caching support in value-log!

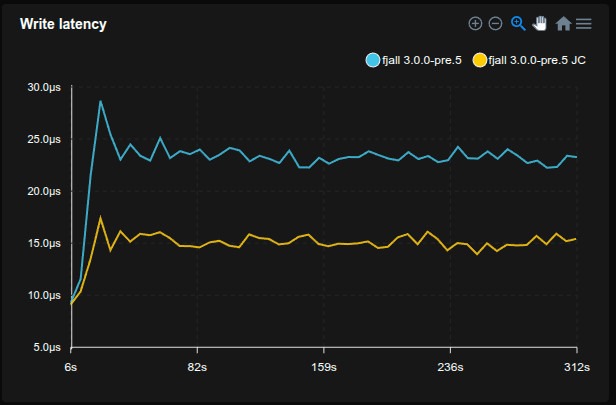

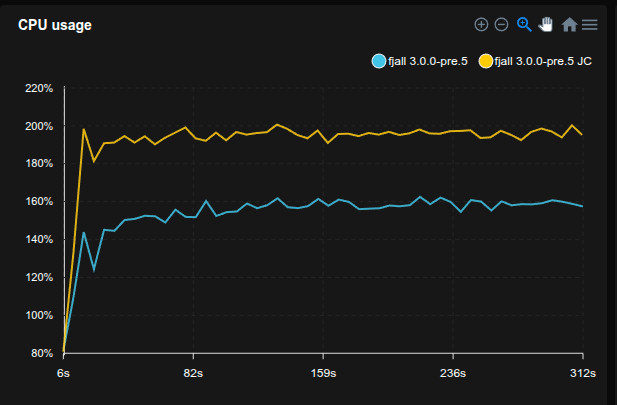

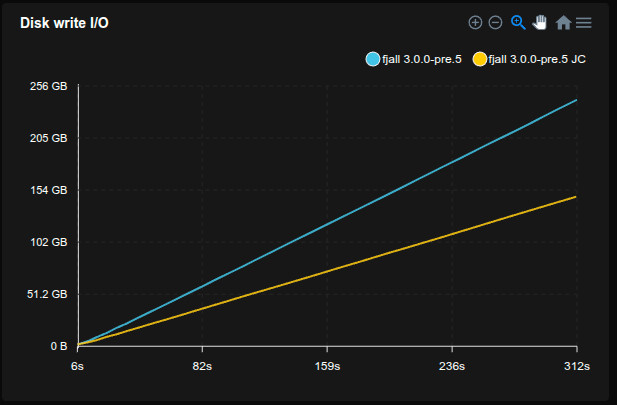

Journal compression

By default, large values will now be compressed when written to the journal. Even in the case of key-value separation, large values (blobs) still need to be written once to the journal. If blobs are pretty compressible, that can reduce write I/O by trading in some additional CPU per insert. Can be disabled.

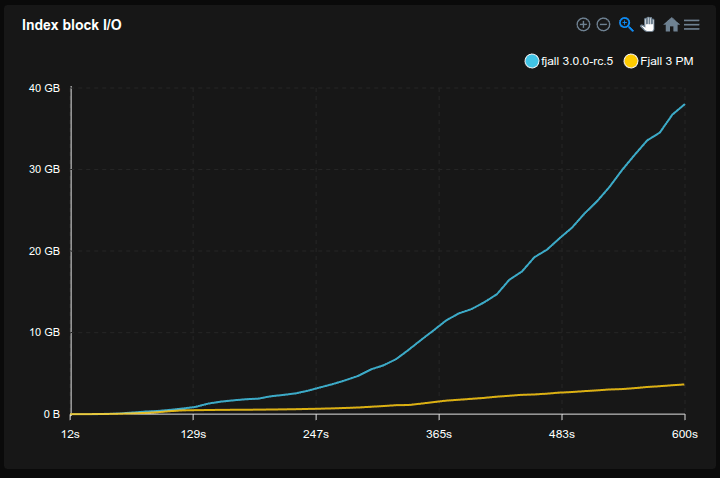

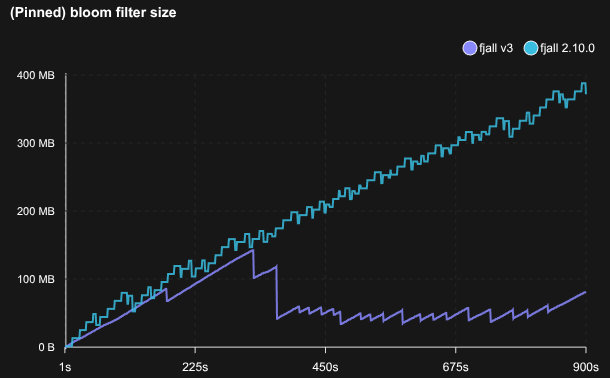

Unpinning filters & indexes

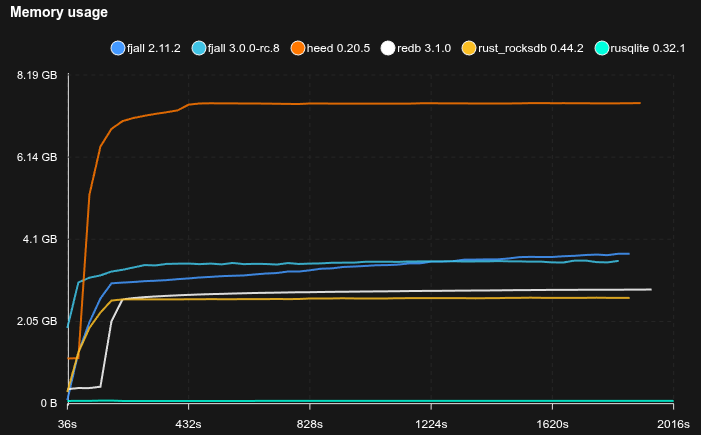

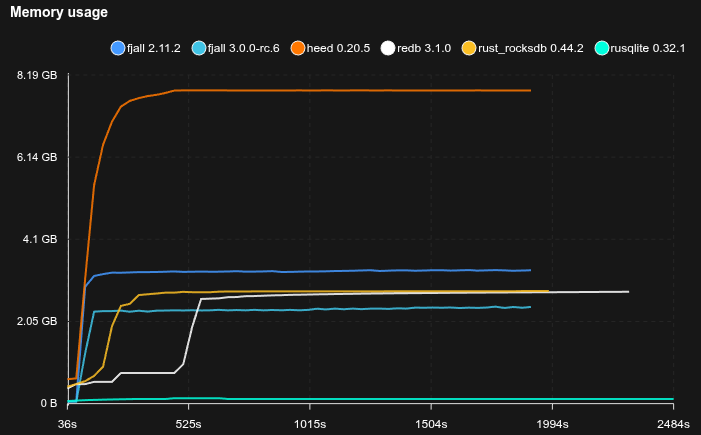

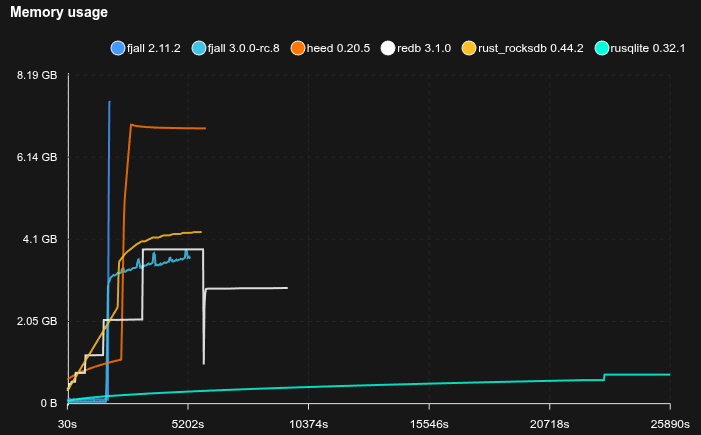

In V1 & V2, bloom filters for all disk tables were always pinned in memory.

That’s generally nice for minimizing cache lookups and disk IO, however, for very large databases and a non-uniform read distribution, the filters can take up memory that could be used to cache other blocks, plus it implicitly coupled the maximum database size (in # keys) to the available memory, roughly num_keys = (RAM - cache_size - other_overhead) / 10 bits.

We can instead choose to not require filters to be loaded. In that situation a point read will first try and get the filter from the block cache; if not found, it will load the filter from disk and cache it.

This dramatically reduces memory usage for very large databases, while being more flexible about paging in and out blocks that are actually “hot”.

By default, L0 and L1 filters are still pinned in memory to avoid them ever getting kicked out of the cache, because they are very small and read very frequently.

This change also speeds up database recovery, because most filters do not need to be eagerly loaded on startup.

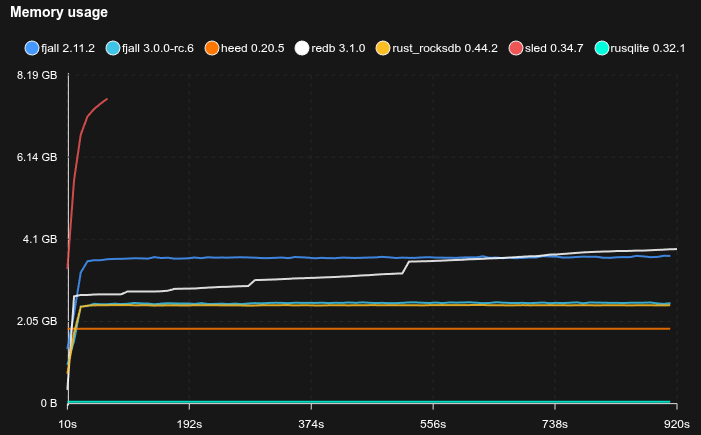

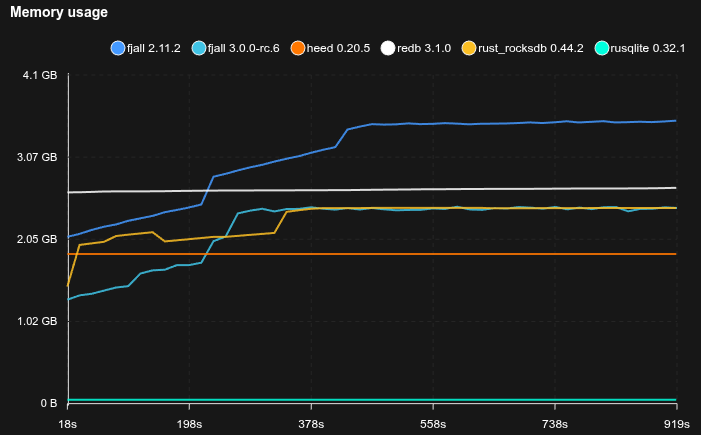

The effect is quite obvious: in a write-only workload, memory pressure does not increase linearly anymore, because filter blocks will be paged out as tables reach deeper levels.

The same applies to index blocks. While not as large as filters, very large databases can still have quite large indexes, which can now also be paged out as needed.

Fluid configuration

The level structure of LSM-trees inherently structure it such that most data is stored in the deeper, larger levels, and more recent, hot data is stored in the upper, smaller levels. This allows us to tweak the levels differently to optimize for read, storage and write costs. For instance, RocksDB allows setting the compression type per level; setting it to a lightweight compression type in the upper levels (e.g. LZ4), which are comparatively small, speeds up reads and writes, while only trading in comparatively little disk space.

But the way this is done is limited, and inconsistent.

For example, set_compression_per_level conflicts with set_bottommost_compression_type, set_compression_type and set_min_level_to_compress, so it’s hard to see what option is prioritized, and bloats the number of configuration options.

Furthermore, this per-level configuration is very limited: it basically only exists for compression.

So why not make use of the fluid nature of the LSM-tree architecture, and make per-level configuration consistent?

So here we are, almost all keyspace configurations can now be controlled per level.

But chances are, you do not really need to touch configuration, except maybe the main knobs such as the block cache capacity.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of examples:

Fine-tuning compression algorithms

We can also set the compression algorithm & level to use per level:

use fjall::{KeyspaceCreateOptions, CompressionType, CompressionPolicy};

let opts = KeyspaceCreateOptions::default()

.data_block_compression_policy(

CompressionPolicy::new([

CompressionType::None, // L0

CompressionType::None, // L1

CompressionType::Lz4,

CompressionType::HeavyCompression, // just an example

CompressionType::VeryHeavyCompression,

])

);

let keyspace = db.keyspace("items", opts)?;L0 and L1 only store ~512 MB of data by default, so skipping compression here can speed up reads & writes without losing a lot of disk space.

To set all levels, repetitive statements can be replaced with:

use fjall::{CompressionPolicy, CompressionType::Lz4};

let opts = KeyspaceCreateOptions::default()

.data_block_compression_policy(CompressionPolicy::all(Lz4));

// or

let opts = KeyspaceCreateOptions::default()

.data_block_compression_policy(CompressionPolicy::disabled());Skipping filters in the last level

For huge databases, filters can take a considerable amount of space (~10 bits per key by default, so ~1.25 GB per 1 billion keys). However, if we expect point reads to generally find an item eventually, filters in the last level are useless because we know they will get a hit anyways (filters are supposed to filter out non-existing keys). Unluckily, the last level also contains the most data (on average 90% of all data), meaning disabling filters in the last level reduces the size of filters by 90%, reducing pressure on the block cache and using less disk space.

expect_point_read_hits is a hint given to the storage engine that you know that your workload generally finds items when using get(), contains_key() or size_of():

use fjall::{KeyspaceCreateOptions, FilterConstructionPolicy, filters::Bloom};

// this is basically RocksDB's optimize_filters_for_hits = true

let opts = KeyspaceCreateOptions::default()

.expect_point_read_hits(true);

let keyspace = db.keyspace("items", opts)?;Using partitioned indexes/filters

Similar to the filters, we can choose whether to fully load block indexes/filter or not.

If not fully loaded, only a lightweight top-level index will be loaded instead, and index/filter blocks will be cached and loaded on demand.

By partitioning indexes/filters, we:

- only need to load a partition (e.g. 4K) of a block index/filter in case of a cache miss, reducing read I/O compared to a uncached full index/filter

- are able to page in only parts of a table’s block index/filter (instead of all of it)

So partitioned indexes/filters are advantageous in situations where we expect that we do not have enough block cache capacity to cache most of our indexes/filters.

use fjall::{KeyspaceCreateOptions, PartitionPolicy, BlockIndexMode};

let opts = KeyspaceCreateOptions::default()

.index_partitioning_policy(

PartitionPolicy::new([

false,

false,

false,

true,

])

);

let keyspace = db.keyspace("items", opts)?;Goodbye Miniz

miniz_oxide support was retired and will be replaced by zlib-rs in the near future.

zlib-rs is a newer, faster Rust implementation of zlib.

On GitHub: https://github.com/fjall-rs/lsm-tree/pull/155

Less strict keyspace names

Keyspace names now don’t have to be filename-safe. Internally, keyspace names are mapped to an integer (Keyspace ID), which is monotonically increasing.

Database locking

V3 now uses Rust’s new file locking API to exclusively lock a database to protect it from multi-process access (which is not supported).

MSRV

The MSRV has increased quite dramatically from 1.75 to 1.91 to remove a lot of legacy workaround for code that was not possible with old rustc versions (such as std::path::absolute or file locking mentioned previously).

V2->V3 migration

There is a migration tool to migrate a V2 “keyspace” to a V3 “database” from one folder to another:

cargo add \

--package fjall_v2_v3_migrator \

--git https://github.com/fjall-rs/migrate-v2-v3use fjall_v2_v3_migrator::{DefaultOptionsFactory, migrate};

pub fn main() {

migrate("v2_folder", "v3_folder", DefaultOptionsFactory).unwrap();

}

// By implementing a custom options factory, you can configure keyspaces

impl OptionsFactory for MyOptionsFactory {

fn get_options(&self, keyspace_name: &str) -> fjall3::KeyspaceCreateOptions {

// Match on keyspace_name and build its Options

}

}Looking back and looking ahead

The very first Git commit for what is now fjall dates back to April 6th, 2022 - then called rust-lsmt-prototype (very original name).

Initially it was a just a testing ground for building the very essential components of an LSM-tree (SSTables, Memtable, …).

The very first release for lsm-tree came in December 2023, after I found that there was no proper LSM-tree crate out there for Rust, and I had the basics working.

Shortly after, I decided to split the lsm-tree crate into its core backing storage (the LSM-tree), and the overarching fully featured storage engine (fjall).

In some way, the pre-Fjall lsm-tree crate was more in line with LevelDB’s architecture (a single keyspace + log), while Fjall now has significant overlap with RocksDB’s architecture.

I agree with many of RocksDB’s architectural decision (not so much with their naming or choice of language).

On the other hand, I did not want to just rebuild RocksDB.

Getting even somewhat close to 100% feature parity and compatibility with it and THEN chasing compatibility in the future would just be a huge source of pain.

Fjall v1 was released in May 2024, pretty quickly followed by v2 in September 2024. Releasing v2 was the first step to the project having actual exposure, going from ~200 GitHub stars to 1’000 in 7 months, just as I had started finishing the very first, initial steps for V3.

The entire Fjall code base (fjall + lsm-tree + byteview + sfa) currently sits at around 42k LoC (including inline tests & doctests), pretty comparable to LevelDB’s code size (~29k LoC), considering LevelDB has less features.

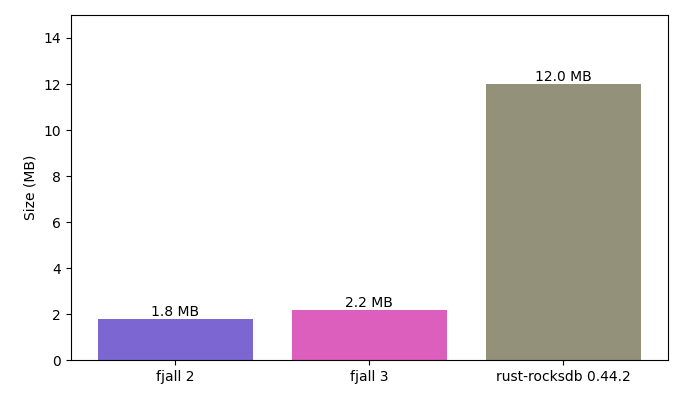

RocksDB has become a huge code base, sitting at around ~700k LoC, which is very evident in its compile times:

My Ryzen 9950X3D needs around 40s (pinned at 100% usage over all its cores) to compile a “Hello World” Rust project using RocksDB, building a ~12 MB binary.

Embedding Fjall v3 currently takes around 3.5s, and gives you a ~2.2 MB binary, though binary size hasn’t been a priority as of now.

RocksDB is not 10x more feature rich, and it mostly definitely is not 10x faster; whether RocksDB’s huge size is justified or not, decide for yourself.

I want a lean and reliable log-structured key-value storage engine, and I believe that a) Rust is the best language to build it with, and b) it can be achieved without needing half a million lines of code. Also, Fjall is an EU 🇪🇺 project, that’s all the rage right now, right?

Where to go from here?

There are still some major features that are missing, all of which can be incrementally implemented without breaking changes:

Single delete

Single deletes are essentially implemented, and are available as a hidden, experimental API. Will be released soon.

On GitHub: https://github.com/fjall-rs/fjall/issues/56

Prefix filters

Prefix filters can improve read performance for prefix() queries, though they need a bit of manual configuration based on the key schema used.

On GitHub: https://github.com/fjall-rs/lsm-tree/pull/151

Compaction filters (mappers?)

Compaction filters allow lazily dropping or changing data based on custom logic (e.g. TTL), without having to do scans through the database.

On GitHub: https://github.com/fjall-rs/lsm-tree/pull/225

Zstd compression support

Zstd is a great, very flexible, compression algorithm.

PSA: Trifecta Tech Foundation is working on a Rust-based zstd implementation.

Checkpoint backups

Checkpointing allows quickly copying a database to a new location. If the location is the same file system, most data can be hard linked, which is very fast. By taking advantage of tables being immutable, backups can be made incrementally.

Would be very nice for fast incremental, on-line backups of a database.

On GitHub: https://github.com/fjall-rs/fjall/issues/52

Merge operator

Merge operators allow efficient read-modify-write operations by not reading at all.

On GitHub: https://github.com/fjall-rs/lsm-tree/issues/104

Range deletions

Range deletions allow deleting a range [min, max] of KVs in O(1) time.

But they make the read path more difficult, and need a lot of attention to detail, making it probably the hardest feature to implement in this list.

On Github: https://github.com/fjall-rs/lsm-tree/issues/2

Encryption

Block-level encryption would be pretty easy to implement and may be desirable for some applications.

CLI

An interactive CLI to inspect and verify (check for corruption) Fjall databases would be nice.

Open Source

If you’ve actually read this far, I will take the opportunity to remind you you can sponsor the project on GitHub. More importantly, I want to redirect you to a couple of open-source projects that make my life easier in one way or another. I am a strong believer in open source, and that maintainers are not reimbursed enough.

- SolidJS: https://github.com/solidjs/solid

- atuin: https://atuin.sh/

- Biome: https://github.com/biomejs/biome

- quick-cache: https://github.com/arthurprs/quick-cache

- nextest: https://github.com/nextest-rs/nextest

- cargo-mutants: https://github.com/sourcefrog/cargo-mutants

- xxhash: https://github.com/DoumanAsh/xxhash-rust

- lz4_flex: https://github.com/PSeitz/lz4_flex

Also, thanks to @zaidoon1 for sending a boat load of PRs during the development of 3.0.0.

Contributions are as always welcome, but for the forseeable future active development on new features will mostly wind down going into 2026.

Benchmarks

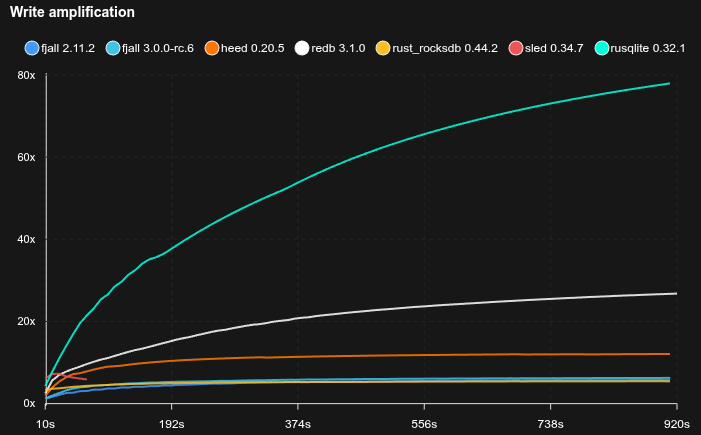

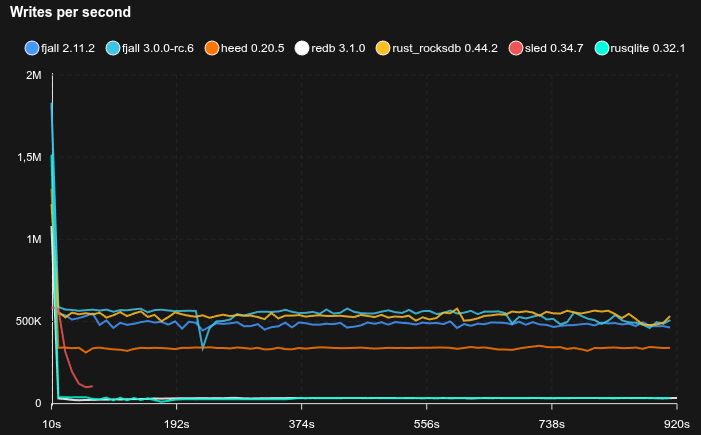

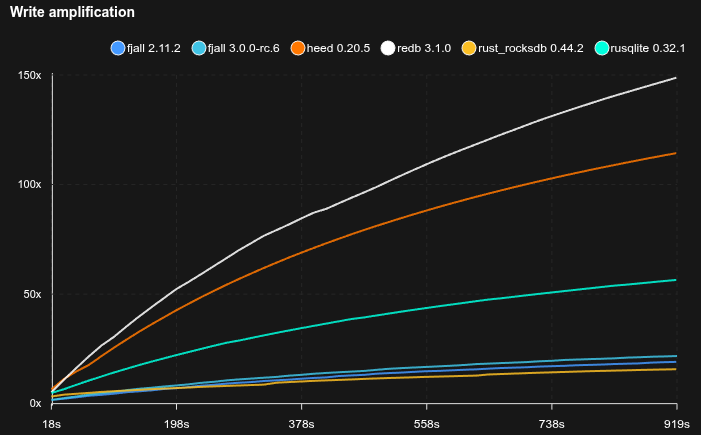

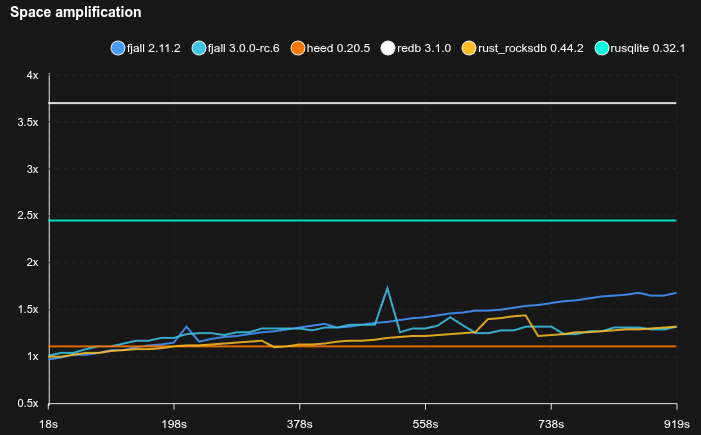

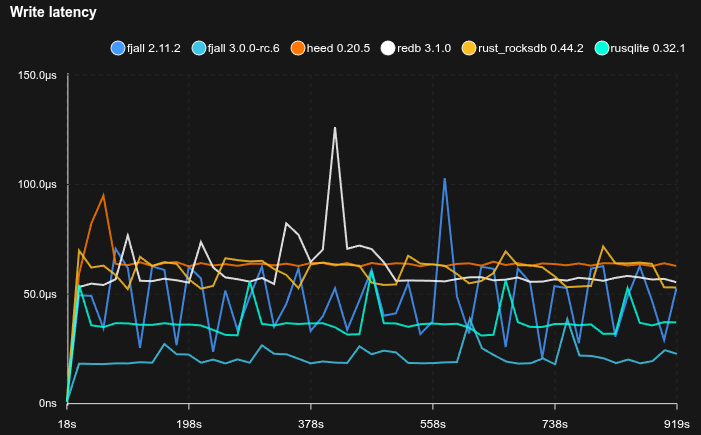

Don’t take benchmarks for granted, and measure for your own workload and hardware yada yada.

Testing hardware

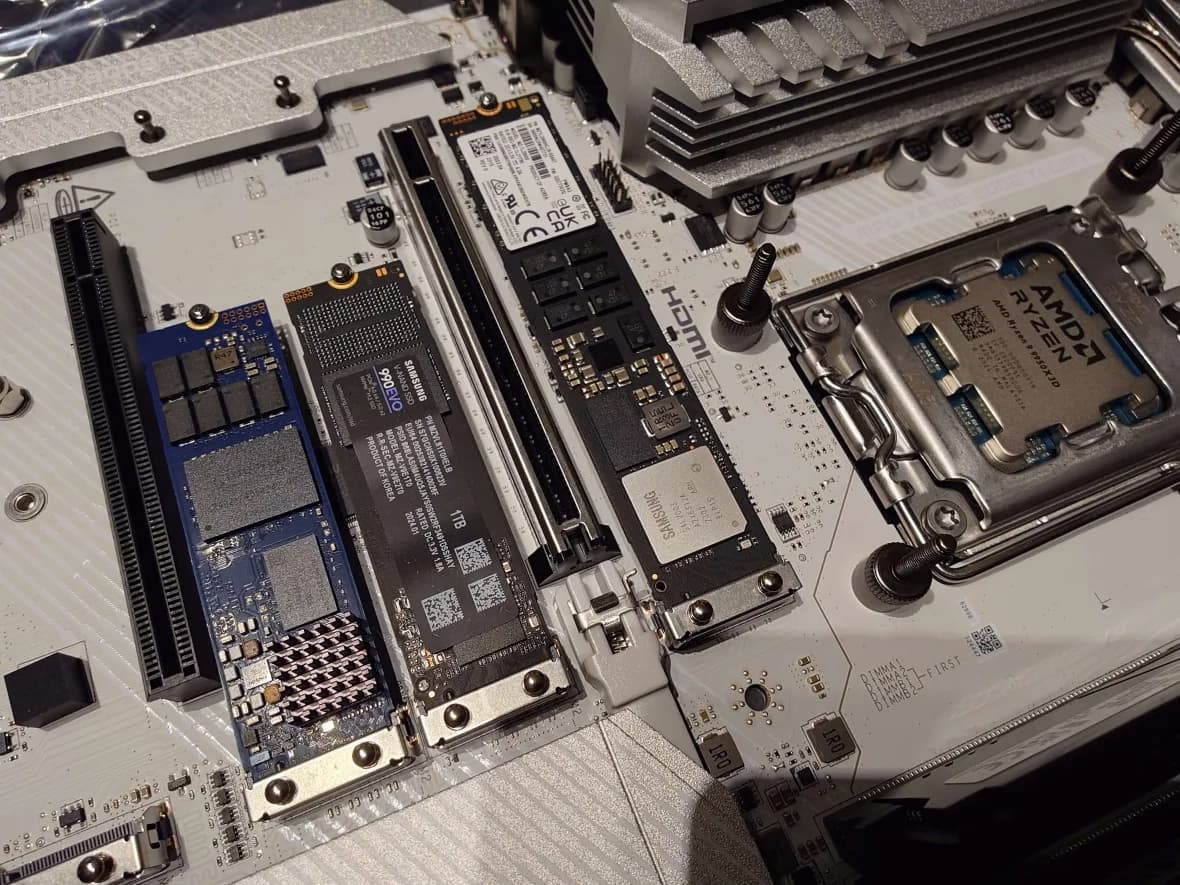

All benchmarks were performed on

- a Ryzen 9950X3D

- 64GB of RAM, artificially limited to 8 GB using

systemd - ext4 on a Kingston DC2000B (960 GB), emptied before every run

Other backends

Sled

Sled is a full-Rust Bw-tree inspired library and by far the most popular Rust-based key-value store. I wouldn’t really compare Sled here because it is in alpha stage and its rewrite is not completed either, but it is so well known in the world of Rust KV stores, I will still include it for reference.

ReDB

ReDB is a full-Rust B-tree based library inspired by LMDB, and probably the most well known one after sled.

Compared to LMDB it does not use memory-mapping and has less specialized features (such as DUPSORT), but it has a more Rust-y API with better support for types.

SQLite

SQLite is not a key-value store, but it is still included to give a rough comparison to the most ubiquitous embedded SQL database out there.

It is implemented in C.

In all benchmarks, WAL mode is used.

Here, SQLite is used in conjunction with rusqlite and r2d2.

LMDB

LMDB is the database made for OpenLDAP, implemented in C, and is based solely around memory mapping and copy-on-write operations.

For this reason, setting the cache size does nothing, because LMDB has no user-space page cache.

The heed wrapper crate by Meilisearch is used here; it is not an official Rust API, but endorsed by the LMDB author.

RocksDB

RocksDB is Meta’s (formerly Facebook) fork of Google’s LevelDB, and implemented in C++.

The rust-rocksdb crate is used, which is community-maintained.

Considerations

mimallocwas used in all benchmark runs- LMDB and SQLite do not perform checksum checks when retrieving pages from disk, which may make them a little bit faster by using a bit less CPU per IO

- The benchmark suite and metrics take around 1-10% of the runtime

- LMDB uses memory mapping - that means the memory shown in the benchmark is not its resident set size (RSS); so the kernel can decide to page out the memory if needed. That’s why it can always use 100% of memory as cache; for the other engines, they use a user-space cache, while the rest of memory can be used by the kernel to cache disk pages; SQLite… I don’t know how it works but its memory is maybe not shown correctly for some reason

- The run will abort if 7+ out of the 8 GB of RAM is used; this is to prevent the benchmark exiting with

Terminatedin case of memory bloat (e.g. sled)

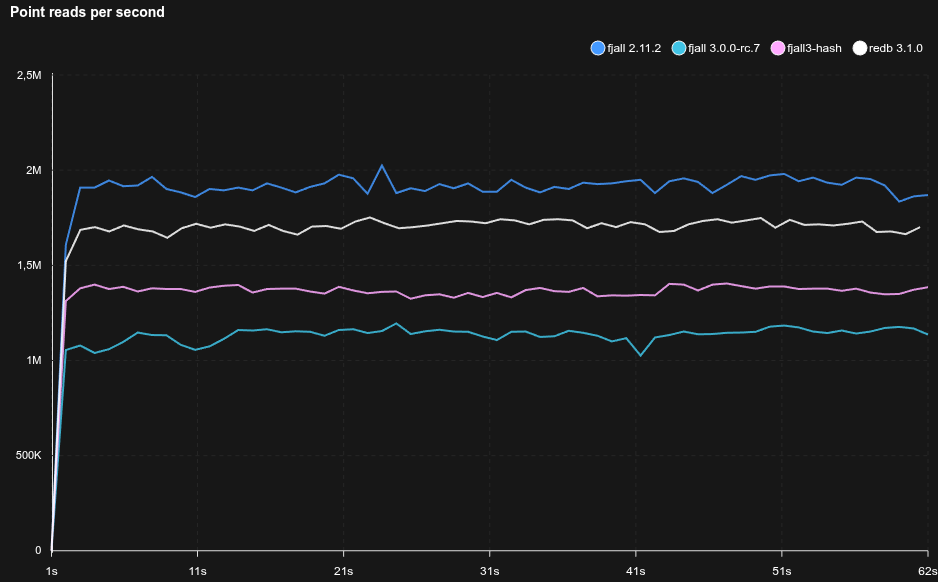

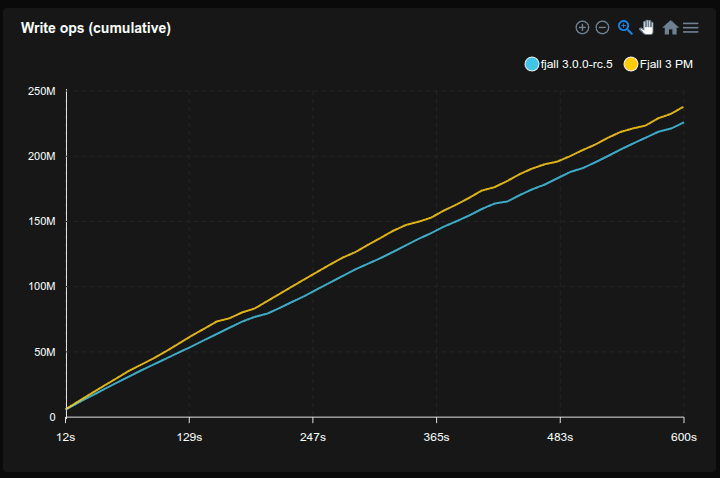

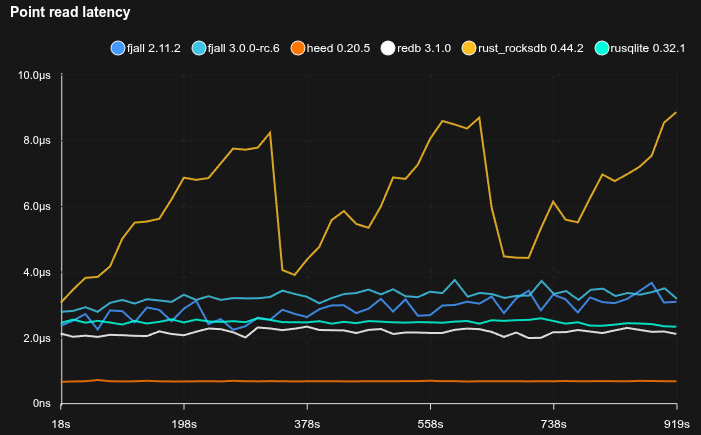

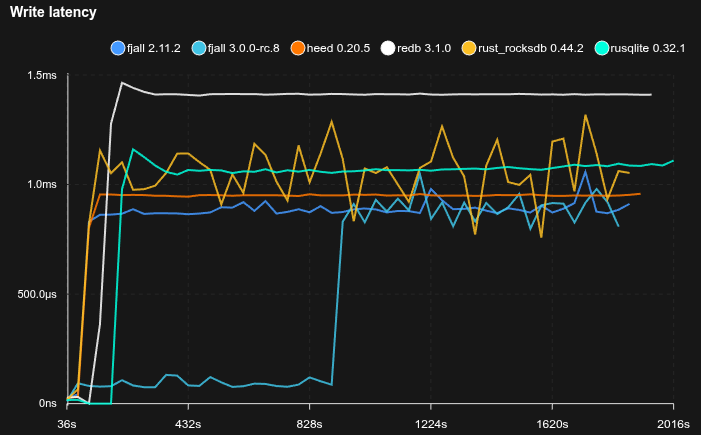

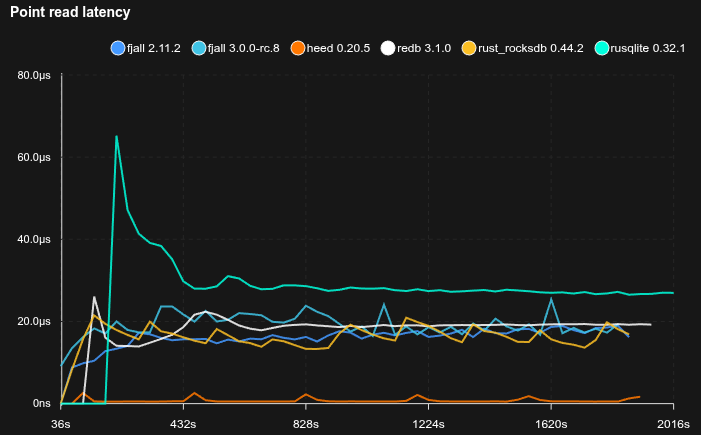

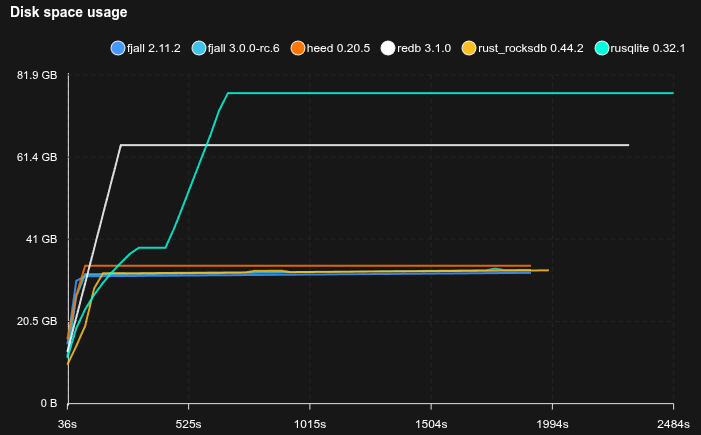

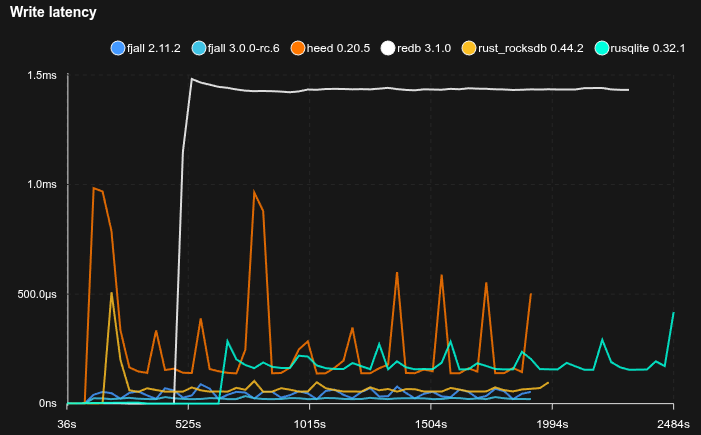

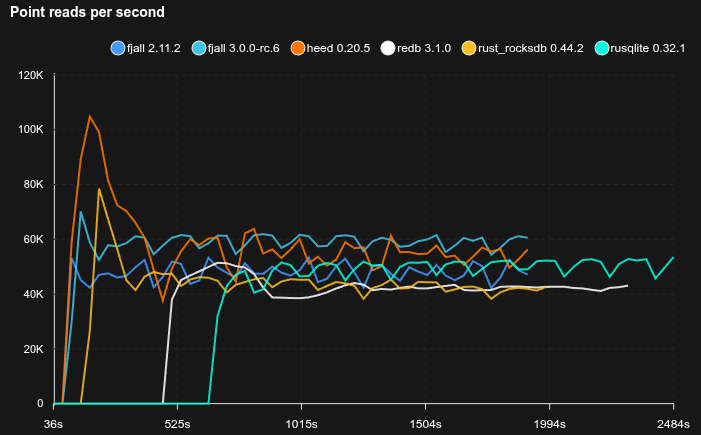

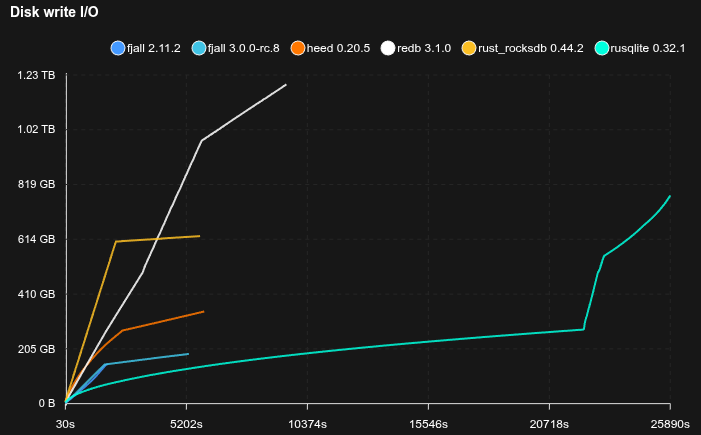

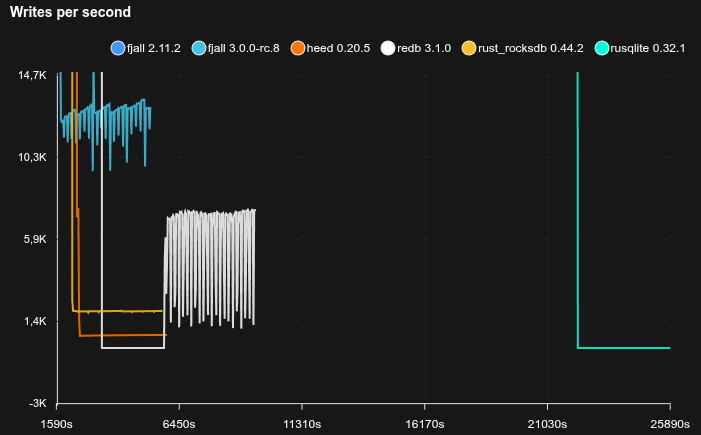

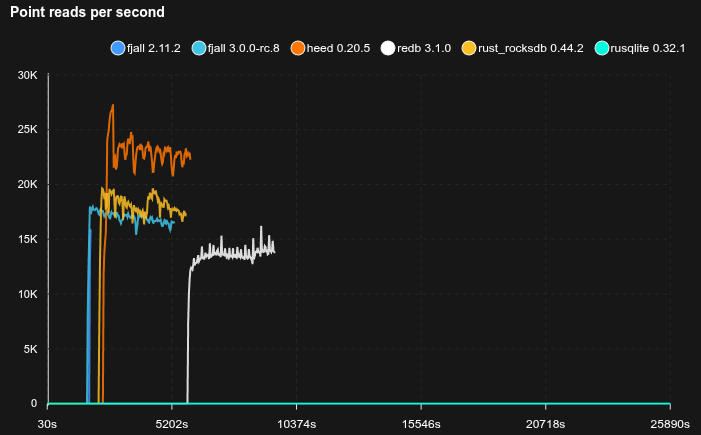

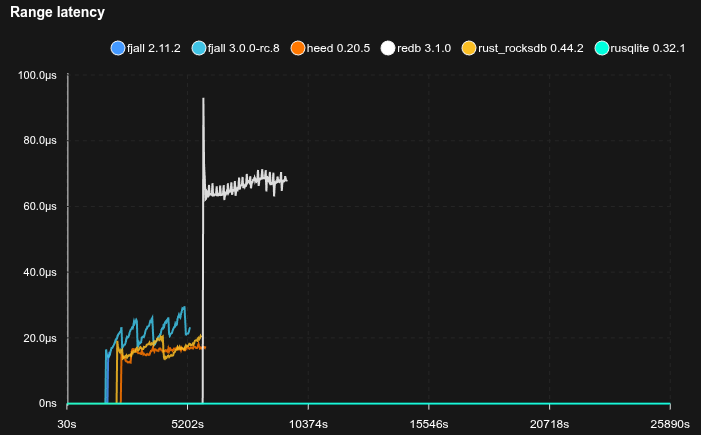

Eventually durable writes with point reads (YCSB A-like)

- ReDB uses the

Nonedurability level; Heed usesMDB_NOSYNCwhich may not be safe to use; SQLite usesPRAGMA synchronous=NORMAL - 10 million KVs are pre-loaded

- 50% of operations are random point reads, 50% are random updates

- Key size is 16 bytes, value size is 100 bytes

- Caches are set to 2 GB

Synchronous writes with point reads (YCSB B-like)

- Sled is not included because it does not reliably fsync

- 10 million KVs are pre-loaded

- 95% of operations are random point reads, 5% are random updates

- Key size is 16 bytes, value size is 100 bytes

- Caches are set to 2 GB

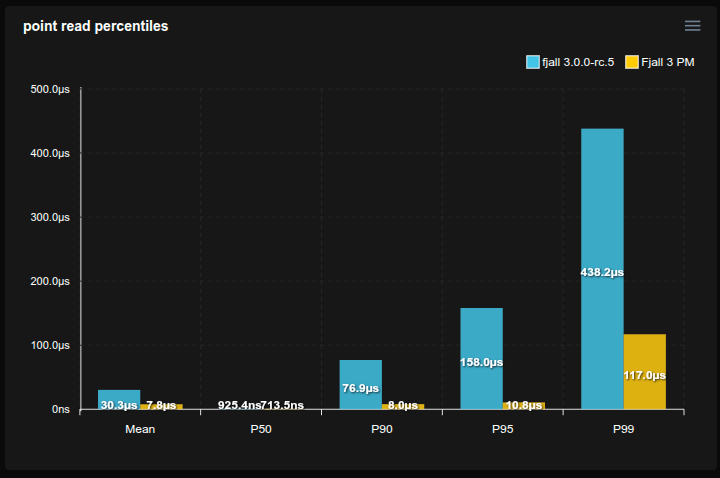

4K random values with point reads

- Caches are set to 2 GB

- 95% of operations are Zipfian point reads, 5% are random updates

- Fjall uses key-value separation with default settings; RocksDB uses BlobDB with default settings

- Journal/WAL compression is disabled

- Sled is not included because it does not reliably fsync

- The database is pre-loaded with 10 GB of data (2.5M blobs)

Medium database with YCSB-B like workload

- Sled is not included because it does not reliably fsync

- 100 million KVs are pre-loaded

- 95% of operations are Zipfian point reads, 5% are random updates

- Key size is 16 bytes, value size is 200 bytes

- Caches are set to 2 GB

Feed workload

- Simulates a workload similar to a social media feed, e.g. Bluesky

- Each user has a profile (

<user_id>#p) and a feed of posts (<user_id>#f#<post_id>) - 50 million users are pre-loaded with 50 posts each

- Caches are set to 2 GB

- 20% of requests write a post, 80% read a profile and its 20 latest posts (using a prefix scan)

- Sled is not included because it does not reliably fsync

SQLite is really not happy with this workload, basically stopping to work completely, but allocating tons of disk space (maybe there’s something wrong with how it’s used, but it’s not exactly transparent).

Discord

Join the discord server if you want to chat about databases, Rust or whatever: https://discord.gg/HvYGp4NFFk

Interested in LSM-trees and Rust?

Check out fjall, an MIT-licensed LSM-based storage engine written in Rust.